TL;DR

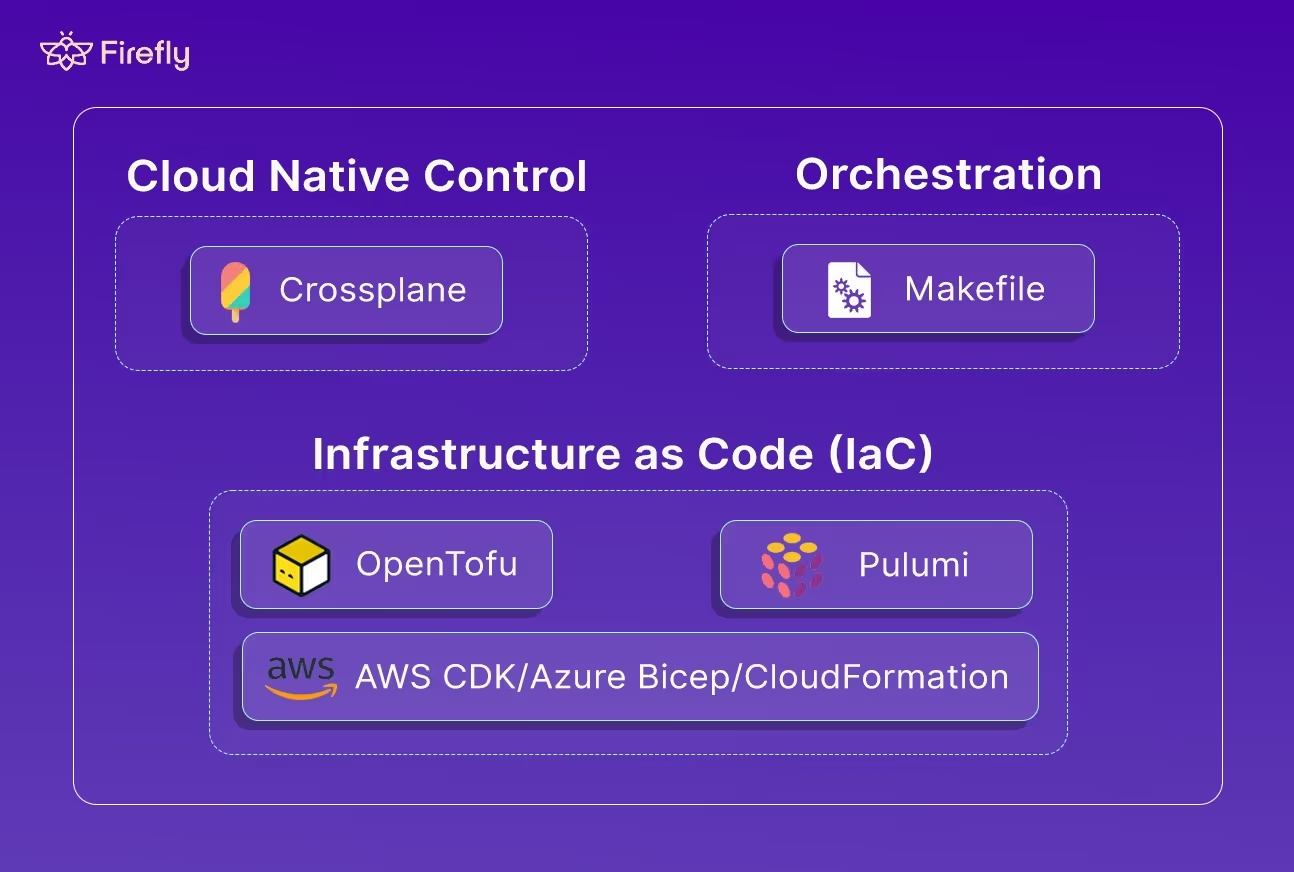

- HashiCorp’s license change pushed enterprises to seek open, vendor-neutral IaC alternatives like OpenTofu, Pulumi, and Crossplane.

- OpenTofu offers a drop-in Terraform replacement under CNCF governance, ensuring long-term openness and compatibility.

- Pulumi enables IaC in real programming languages for better reusability, testing, and developer experience.

- Crossplane extends IaC into Kubernetes-native, continuously reconciled infrastructure, ideal for GitOps environments.

- Firefly unifies visibility and governance across multi-IaC stacks, providing drift detection, compliance, and cost control from one platform.

For a long time, Terraform has been the standard for Infrastructure as Code. It gave teams a clean, declarative way to describe infrastructure, a massive provider ecosystem, and a common language for provisioning across AWS, Azure, and GCP. It became the default choice for DevOps teams building at scale.

But things changed fast after HashiCorp’s switch from MPLv2 to a proprietary BUSL license. That single move forced enterprises to rethink long-term lock-in and the sustainability of their IaC tooling. The open-source community didn’t wait; within months, OpenTofu emerged under the CNCF umbrella as a true open alternative. Vendors followed suit: JFrog even announced OpenTofu support in Artifactory on X (Twitter), acknowledging that teams were actively shifting their Terraform pipelines toward open-governed ecosystems.

Meanwhile, infrastructure sprawl kept growing. Most large environments now span multiple clouds, with hundreds of workspaces, nested modules, and hand-crafted wrappers. Terraform’s simplicity, once its greatest strength, started to show cracks. Managing state files, detecting drift, enforcing policies, and handling cross-team governance all became ongoing pain points.

So the question is no longer “How do we use Terraform better?” but rather “Is Terraform still enough for today’s multi-cloud enterprise?”

In this post, we’ll break down why enterprises are re-evaluating Terraform, what the best alternatives look like, including OpenTofu, Pulumi, and Crossplane, and how governance layers like Firefly help unify visibility, drift detection, and policy enforcement across all these tools.

Why Enterprises Are Re-Evaluating Terraform

Terraform’s dominance came from being open, stable, and predictable. But as the modern cloud environment evolved, with dozens of teams, hundreds of accounts, and a mix of tools, some of those foundational assumptions began to break down. The past year made that clear.

Licensing & Vendor Lock-In Concerns

HashiCorp’s move from MPL 2.0 to the Business Source License (BSL) in August 2023 changed Terraform’s foundation. Under the new license, Terraform’s code is still public, but no longer truly open source; commercial use now carries restrictions. Teams embedding or offering Terraform-based services may need a commercial agreement, while internal use stays unaffected.

For enterprises, that’s not a pricing issue; it’s a control issue. IaC tools live deep inside CI/CD, compliance, and provisioning pipelines, often for years. A license shift like this introduces long-term governance risk: future updates could carry terms that don’t align with your platform strategy.

That’s why many organizations pinned to Terraform v1.5.x (the last MPL-licensed release) or switched to OpenTofu, the CNCF-governed open fork that stays config-compatible. The move isn’t about ideology; it’s about ensuring your automation stack stays future-proof and free from vendor dependency.

In short, Terraform may still be free, but it’s no longer fully open.

HCL Limitations for Real-World Engineering

Terraform’s HCL language keeps infrastructure definitions clean, declarative, and easy to reason about. It’s great for building predictable, well-defined environments. But once your infrastructure needs dynamic logic, environment-specific customization, or large-scale reuse, the language starts to feel restrictive.

1. Adjustment for Developers

HCL follows a declarative model; you describe the desired state, and Terraform figures out the steps to get there. That’s ideal for static resources, but limiting when infrastructure logic needs conditional or programmatic control. Engineers coming from languages like Python, Go, or TypeScript, and familiar with tools like Pulumi, are used to writing code that branches, loops, or reuses functions.. HCL doesn’t support that kind of procedural control, so teams often push dynamic behavior into wrappers, CI pipelines, or other alternative tools like Terragrunt to fill the gap.

2. Limited Reuse and Control Flow

HCL supports for and if expressions for transforming or filtering data, but they’re scoped to expressions, not reusable logic. You can’t define your own functions or dynamically control how modules behave at runtime. As infrastructure grows, engineers end up copying modules or stacking nested conditionals to handle variations across environments or accounts. That works short-term, but it becomes messy and hard to maintain at scale.

3. Late Validation and Error Discovery

HCL performs type checking and validation only during the terraform plan or apply phases. There’s no compile-time validation, so mistakes, like passing a string instead of a boolean, aren’t caught until Terraform runs. Static analysis tools like tflint and editor plugins help, but feedback still lags compared to languages that support type safety natively. This often leads to slow feedback loops and failed plans late in the pipeline.

4. Rigid Module Behavior

Modules bring organization, but they don’t scale dynamically. You can’t create modules programmatically or parameterize them flexibly. For example, backend configuration and workspace logic can’t be templated easily, and cross-module references must be wired manually. When teams manage multiple environments, these static constraints lead to duplication and small inconsistencies that add up to real drift over time.

5. Lack of Built-In Testing

Terraform doesn’t include a native testing framework. There’s no direct way to validate module behavior without running a plan or deploying resources. Teams rely on tools like Terratest or manual plan reviews to catch regressions, which slows feedback and adds human overhead. Small changes that would be unit-tested in application code can only be verified after real resources are provisioned, increasing risk and iteration time.

6. Shift Toward Code-Native IaC

To get around these limits, many teams have started using Pulumi, AWS CDK, or CDK for Terraform (CDKTF). These tools let you define infrastructure in real programming languages such as TypeScript, Python, or Go, giving you loops, functions, unit tests, type checking, and full IDE integration. They still produce declarative cloud resources but give engineers the flexibility and developer experience that large-scale infrastructure projects demand.HCL remains a solid choice for clear, consistent infrastructure definitions, but its static structure and lack of early validation or testing make it less effective for complex, fast-moving, or heavily automated environments.

Governance and Visibility Gaps

Open-source Terraform doesn’t provide native governance, there’s no RBAC, audit logging, or policy enforcement out of the box. Most teams rely on manual pull-request reviews, tflint, or OPA policies baked into CI. This works in small setups, but it breaks down when you scale to hundreds of modules or distributed teams.

Terraform Cloud and Enterprise versions add policy-as-code and access controls, but they only cover Terraform-managed resources, which comes with additional cost in their paid plans. Anything deployed through Pulumi, CDK, or console changes sits outside that visibility.

This creates blind spots in compliance and cost tracking. Teams can’t easily answer basic governance questions:

- Which resources aren’t managed by IaC?

- Who last modified a production resource?

- Are all resources tagged and compliant with policy?

For large organizations, these gaps mean more audits, manual enforcement, and longer change cycles, all of which slow down engineering velocity.

Multi-Cloud and Tool Fragmentation

In reality, no enterprise runs a single IaC tool.

- AWS teams often use CloudFormation or CDK,

- Azure teams use Bicep,

- And some platform teams use Pulumi or Terraform for multi-cloud layers.

Each tool has its own syntax, lifecycle, and state management model. As these tools overlap, visibility fragments. One team’s Terraform state doesn’t reflect another’s CloudFormation stack or a manually provisioned resource.

Over time, this leads to multi-IaC drift, missing tags, orphaned resources, inconsistent policies, and incomplete cost reporting. Platform and security teams then spend significant time reconciling what exists versus what’s declared, instead of improving automation.

Top Terraform Alternatives: What’s Out There

Terraform has been the default IaC tool for years, but it’s no longer the only mature option. Different teams have different needs; some want open governance, some want richer programming models, and others want deeper integration with a specific cloud or Kubernetes.

Below is a breakdown of the main alternatives that enterprises are adopting, when they make sense, and what trade-offs they bring.

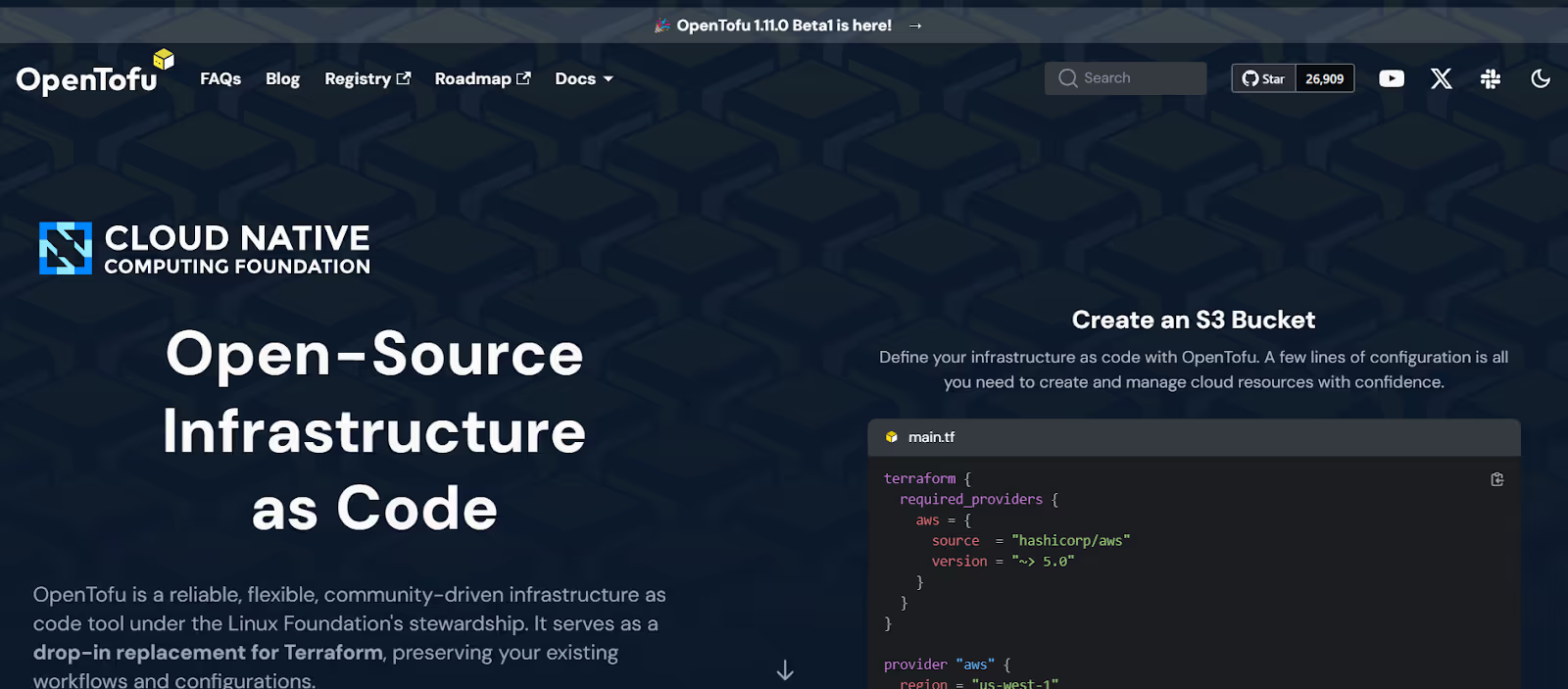

1. OpenTofu

OpenTofu is the community-driven fork of Terraform, created right after HashiCorp changed Terraform’s license from MPL 2.0 to the Business Source License (BSL). It’s now part of the CNCF (Cloud Native Computing Foundation), which guarantees open governance and long-term neutrality.

How it works:

OpenTofu is a drop-in replacement for Terraform up to version 1.5. You can use the same .tf files, providers, modules, and workflows; everything works out of the box. The CLI and state management are identical, and your existing Terraform pipelines continue to function without modification.

Example:

resource "aws_s3_bucket" "example" {

bucket = "example-bucket"

acl = "private"

}This exact code given above works in both Terraform and OpenTofu.

Hands-On: Creating a GCS Bucket with OpenTofu

To see how OpenTofu feels in practice, let’s spin up something simple, a Google Cloud Storage (GCS) bucket. It’s a clean, low-risk way to test how OpenTofu behaves, whether locally or inside a CI sandbox.

Start by installing OpenTofu from opentofu.org. Once it’s in your PATH, verify it with tofu version. If Terraform’s CLI feels familiar, you’ll notice nothing’s really changed; the commands are identical.

Next, authenticate to Google Cloud using gcloud auth application-default login. Once you’re authenticated, grab the example repo and copy the variables template:

cp terraform.tfvars.example terraform.tfvarsThen open the file and set your values, something like:

project = "your-gcp-project-id"

region = "US-CENTRAL1"

bucket_name_prefix = "docs-page-logs"

environment = "dev"Now comes the main part. Run tofu init. You’ll see it pull down the google and random providers, verify signatures, and generate a .terraform.lock.hcl. That lock file’s important; it locks provider versions so your future runs are deterministic.

With initialization done, run:

tofu planYou’ll get a preview that looks familiar:

Plan: 2 to add, 0 to change, 0 to destroy.One random_id for the bucket suffix, and one google_storage_bucket to create the actual bucket. If it looks right, go ahead and apply it:

tofu applyConfirm with yes, and in a few seconds you’ll see:

Apply complete! Resources: 2 added, 0 changed, 0 destroyed.

Outputs:

bucket_gs_url = "gs://docs-page-logs-a8687492"

bucket_name = "docs-page-logs-a8687492"

bucket_self_link = "https://www.googleapis.com/storage/v1/b/docs-page-logs-a8687492"That’s it, OpenTofu just provisioned a fully managed GCS bucket, using the same syntax and flow as Terraform. The only difference? You’re now running on a community-driven engine backed by the CNCF instead of a proprietary license.

When you don't require resources anymore, cleaning up is just as straightforward:

tofu destroyOpenTofu tears everything down cleanly and leaves your workspace ready for the next test. This example sums up what’s great about OpenTofu: everything works exactly as before, but the future of your IaC pipeline is no longer tied to a single vendor’s license or roadmap.

From a dev’s perspective, OpenTofu behaves exactly like Terraform. The key difference is trust and governance; it’s community-led, CNCF-backed, and free from license ambiguity. This gives enterprises confidence to keep building automation and internal tooling on top of HCL without worrying about long-term vendor risk.

When to choose OpenTofu:

- You rely heavily on Terraform but don’t want to be tied to HashiCorp’s BSL.

- You’re building internal platforms or tooling around Terraform and need long-term license safety.

- You want to stay on the same configuration model (HCL) without rewriting your existing codebase.

- You prefer a tool that’s maintained under open governance and backed by CNCF.

OpenTofu is Terraform without the vendor risk. It’s the same engine, same syntax, and same ecosystem, just developed in the open and built to stay that way. The next most relevant alternative is Pulumi

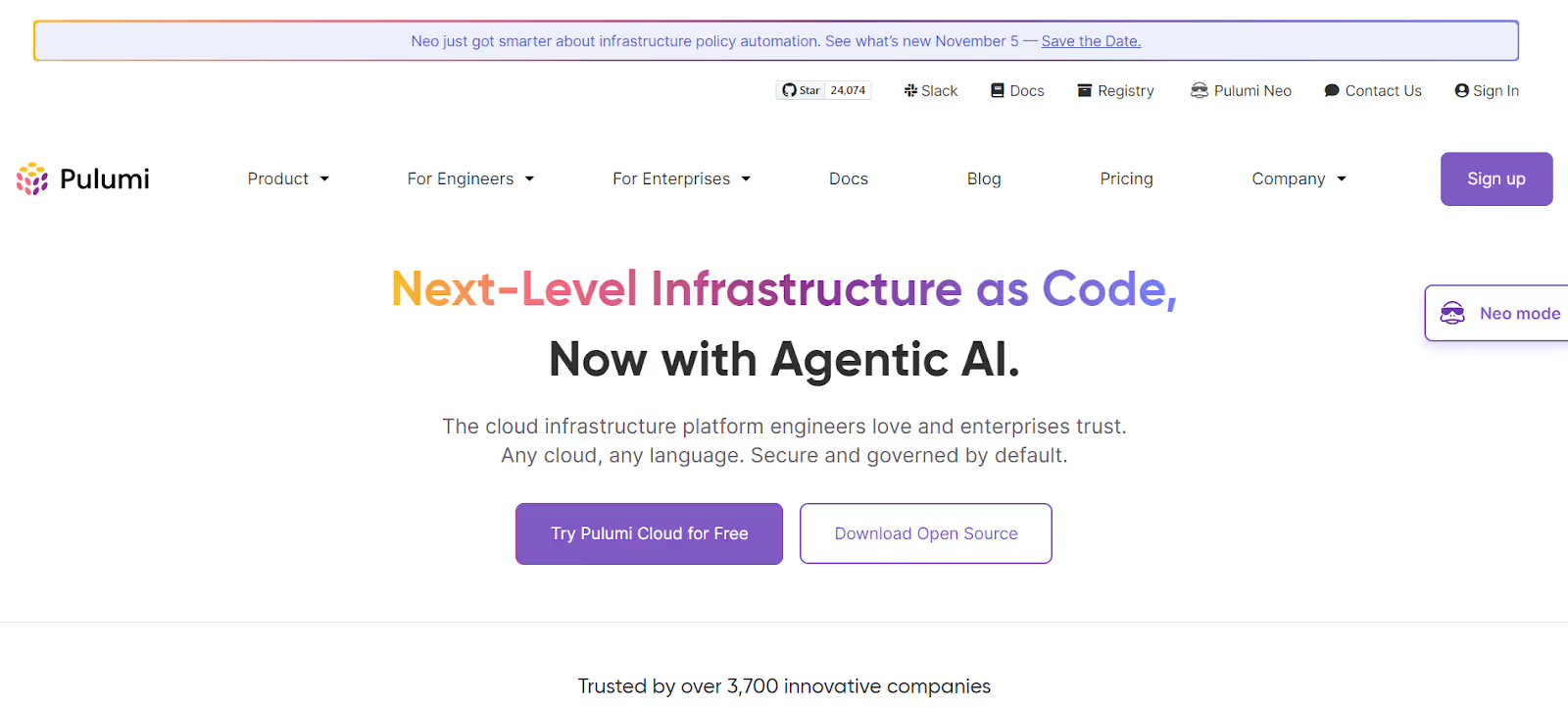

2. Pulumi

Pulumi takes a different approach to Infrastructure as Code. Instead of using a DSL like HCL, it lets you define infrastructure using languages, TypeScript, Python, Go, C#, or Java.

You don’t write declarative config files; you write actual code that describes your infrastructure. That means you can use loops, functions, conditionals, imports, the same language features you already use for applications, but they compile down to the same declarative cloud API calls you’d get from Terraform.

Under the hood, Pulumi uses your cloud provider’s native SDKs (AWS, Azure, GCP, Kubernetes, etc.) to create resources. It stores state remotely in Pulumi Cloud (SaaS) or in self-managed backends such as S3 or Azure Blob Storage.

Hands-On: Creating a GCS Bucket with Pulumi

Pulumi lets you define infrastructure as real code, so let’s see what that feels like with a simple, compliance-ready GCS bucket built using Python and the Google Native SDK.

Setting the Stage

You start by setting up your local Pulumi environment. Once you’ve installed the Pulumi CLI, grab the Python dependencies:

pip install pulumi pulumi-google-nativeAuthenticate to Google Cloud, either with your service account credentials:

export GOOGLE_APPLICATION_CREDENTIALS=/path/to/service-account.jsonOr just log in using gcloud:

gcloud auth application-default loginThen bootstrap a new project:

pulumi new gcp-compliance-pulumiPulumi creates a lightweight project for you, a Pulumi.yaml, a virtual environment, and a __main__.py file. This becomes your infrastructure entry point. Here’s the entire setup in __main__.py. It defines a GCS bucket with uniform access, versioning, and a lifecycle rule to automatically delete older objects.

import pulumi

import pulumi_google_native as gcp

# Load project configuration dynamically

config = pulumi.Config()

project = config.require("gcp:project")

bucket_location = config.get("bucket_location") or "US"

# Define a compliance-focused GCS bucket

bucket = gcp.storage.v1.Bucket(

"compliance-bucket",

location=bucket_location,

uniformBucketLevelAccess=gcp.storage.v1.BucketUniformBucketLevelAccessArgs(enabled=True),

versioning=gcp.storage.v1.BucketVersioningArgs(enabled=True),

lifecycle=gcp.storage.v1.BucketLifecycleArgs(

rule=[

gcp.storage.v1.BucketLifecycleRuleArgs(

action=gcp.storage.v1.BucketLifecycleRuleActionArgs(type="Delete"),

condition=gcp.storage.v1.BucketLifecycleRuleConditionArgs(age=90)

)

]

),

labels={

"managed_by": "pulumi",

"environment": "dev"

}

)

# Export outputs for reference

pulumi.export("bucket_name", bucket.name)

pulumi.export("bucket_self_link", bucket.self_link)

pulumi.export("bucket_url", pulumi.Output.concat("gs://", bucket.name))

This one file defines everything: compliance, lifecycle, and metadata, using plain Python.

Before deploying, configure your project with a few parameters:

pulumi config set gcp:project your-gcp-project-idNow, dry-run the deployment:

pulumi previewYou’ll see Pulumi simulate the plan:

Previewing update (dev)

+ pulumi:pulumi:Stack gcp-compliance-pulumi-dev create

+ └─ google-native:storage/v1:Bucket compliance-bucket createWhen the preview looks good, apply it:

pulumi upPulumi executes the plan, showing live progress as it provisions the bucket:

Updating (dev)

+ pulumi:pulumi:Stack gcp-compliance-pulumi-dev created (8s)

+ └─ google-native:storage/v1:Bucket compliance-bucket created (4s)

Outputs:

bucket_name : "compliance-bucket-eb8ebe3"

bucket_self_link: "https://www.googleapis.com/storage/v1/b/compliance-bucket-eb8ebe3"

bucket_url : "gs://compliance-bucket-eb8ebe3"Outputs:

bucket_name : "compliance-bucket-eb8ebe3"

bucket_self_link: "https://www.googleapis.com/storage/v1/b/compliance-bucket-eb8ebe3"

bucket_url : "gs://compliance-bucket-eb8ebe3"

In a few seconds, the bucket is live, versioning enabled, uniform IAM enforced, lifecycle cleanup set, and tagged for governance. Cleanup if you don't require the resources anymore using:

pulumi destroyPulumi tracks your state, confirms deletions interactively, and cleans up the bucket safely, no manual drift or orphaned resources left behind. This example captures what Pulumi does best: you get real language flexibility, native SDKs, and CI/CD-ready IaC that feels like software development, not static configuration. It’s the same end result as Terraform or OpenTofu, but the workflow feels far more integrated for engineers who already live in Python, TypeScript, or Go.

When to Choose Pulumi

Pulumi fits best when your teams already work heavily in code and you want the same engineering practices for infrastructure that you use for applications.

It’s especially strong when:

- You’re building platform automation or internal developer platforms.

- You need reusable logic, type safety, or unit tests around your IaC.

- You want to integrate IaC directly into existing CI/CD pipelines with modern tooling.

You trade a little simplicity for a lot of flexibility, and in most enterprise environments, that’s a worthwhile trade.

3. Crossplane

Crossplane is a Kubernetes-native Infrastructure-as-Code framework that turns your Kubernetes cluster into a full-blown control plane for managing not just applications, but cloud infrastructure itself, across AWS, Azure, and GCP.

Instead of running any cli tool like Terraform or Pulumi, Crossplane lets you define infrastructure as Kubernetes manifests (YAML) and reconcile them through the Kubernetes API. Every resource (such as an S3 bucket or a GCP database) becomes a custom resource managed by the cluster, versioned, declarative, and API-driven.

While tools like Terraform and Pulumi are CLI-driven and stateful, Crossplane takes a controller-based approach:

- It continuously reconciles the desired state, just like Kubernetes does for pods.

- No external state file, infrastructure state lives in your cluster.

- Enables GitOps workflows with tools like ArgoCD and Flux.

- Turns infrastructure into declarative APIs, so platform teams can expose custom resource definitions (CRDs) for developers — safely and with policy boundaries.

Crossplane lets platform teams build their own Terraform, but fully integrated with Kubernetes and CI/CD.

Hands-On: Creating a GCS Bucket with Crossplane

Let’s look at a minimal flow to provision a GCP bucket using Crossplane.

1. Install Crossplane

You can install it into any Kubernetes cluster:

kubectl create namespace crossplane-system

helm repo add crossplane-stable https://charts.crossplane.io/stable

helm repo update

helm install crossplane crossplane-stable/crossplane -n crossplane-system2. Install the GCP Provider

kubectl crossplane install provider crossplane/provider-gcp:v0.28.03. Configure Provider Credentials

Create a Kubernetes secret with your service account key:

kubectl create secret generic gcp-creds -n crossplane-system \ --from-file=creds=./gcp-key.jsonApply the provider config:

apiVersion: gcp.crossplane.io/v1beta1

kind: ProviderConfig

metadata:

name: default

spec:

projectID: your-gcp-project

credentials:

source: Secret

secretRef:

namespace: crossplane-system

name: gcp-creds

key: creds

4. Create a GCS Bucket

apiVersion: storage.gcp.crossplane.io/v1beta1

kind: Bucket

metadata:

name: crossplane-demo-bucket

spec:

forProvider:

location: US

storageClass: STANDARD

labels:

environment: dev

managed-by: crossplane

providerConfigRef:

name: defaultApply the manifest:

kubectl apply -f bucket.yamlCrossplane will reconcile it in real time:

kubectl get bucketsYou’ll see the bucket provisioned on GCP, just like a native Kubernetes resource.

When Teams Adopt Crossplane

Enterprises typically adopt Crossplane when:

- They’re already Kubernetes-first and want to manage both infra and apps from one control plane.

- Platform teams want to abstract cloud complexity behind simple APIs (e.g., kind: DatabaseInstance).

- They need continuous reconciliation rather than one-time deployments, e.g., auto-healing infra drift.

- They’re building internal developer platforms (IDPs) or GitOps automation pipelines.

4. AWS CDK / Azure Bicep / CloudFormation

When teams operate mostly within one cloud, native Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) tools often fit better than Terraform or Pulumi. These frameworks are maintained by the cloud providers themselves and are built for deep integration. IAM permissions, drift detection, audit logging, and new service support are all available on day one.

AWS CDK: Infrastructure as Real Code

AWS CDK (Cloud Development Kit) lets you write infrastructure using familiar languages, TypeScript, Python, Go, or C#. Under the hood, CDK converts your code into CloudFormation templates, combining the flexibility of real code with the stability of CloudFormation.

Example – S3 Bucket with CDK (Python):

from aws_cdk import (

App, Stack,

aws_s3 as s3,

)

from constructs import Construct

class DemoStack(Stack):

def __init__(self, scope: Construct, id: str, **kwargs):

super().__init__(scope, id, **kwargs)

s3.Bucket(

self, "DemoBucket",

versioned=True,

block_public_access=s3.BlockPublicAccess.BLOCK_ALL,

encryption=s3.BucketEncryption.S3_MANAGED,

removal_policy=3 # DESTROY

)

app = App()

DemoStack(app, "demo-stack")

app.synth()

CDK gives you loops, functions, and imports, the same coding patterns developers already use, while still producing declarative CloudFormation templates for provisioning.

CloudFormation: AWS’s Native Declarative IaC

CloudFormation is the foundation on which most AWS IaC tools (including CDK) are built. It’s a declarative engine that uses YAML or JSON templates to describe infrastructure, and it automatically manages provisioning, dependencies, and rollbacks.

Here’s the same S3 bucket defined directly in CloudFormation YAML:

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: '2010-09-09'

Description: Create an S3 bucket with versioning and encryption enabled

AWSTemplateFormatVersion: '2010-09-09'

Description: Create an S3 bucket with versioning and encryption enabled

Resources:

DemoBucket:

Type: AWS::S3::Bucket

Properties:

BucketName: demo-bucket-${AWS::AccountId}

VersioningConfiguration:

Status: Enabled

PublicAccessBlockConfiguration:

BlockPublicAcls: true

BlockPublicPolicy: true

IgnorePublicAcls: true

RestrictPublicBuckets: true

BucketEncryption:

ServerSideEncryptionConfiguration:

- ServerSideEncryptionByDefault:

SSEAlgorithm: AES256

Deploy with a single command:

aws cloudformation deploy \

--template-file s3-bucket.yaml \

--stack-name demo-stackWhy teams still use CloudFormation:

- Native drift detection (you can run aws cloudformation detect-stack-drift anytime).

- Integrated rollback and dependency handling.

- Built-in audit trails through CloudTrail and AWS Config.

- No external state files, everything lives within AWS.

Its biggest drawback is verbosity; large templates become hard to maintain manually. That’s exactly why CDK exists: it provides programmatic generation of these templates while keeping CloudFormation’s reliability.

5. Azure Bicep: Clean, Native IaC for Azure

Bicep is Azure’s modern IaC language that compiles into ARM templates.

It keeps the declarative structure but simplifies syntax drastically compared to raw JSON-based ARM.

Example – Azure Storage Account:

resource storage 'Microsoft.Storage/storageAccounts@2023-01-01' = {

name: 'bicepstorage${uniqueString(resourceGroup().id)}'

location: resourceGroup().location

sku: {

name: 'Standard_LRS'

}

kind: 'StorageV2'

}Deploy easily with:

az deployment group create \

--resource-group my-rg \

--template-file main.bicepBicep supports parameterization, modules, and tight integration with Azure Policy, making it ideal for enterprises that need compliance baked in.

When to Choose Native IaC Tools

Choose AWS CDK, CloudFormation, or Azure Bicep when:

- You operate primarily in a single cloud (AWS or Azure), which is not possible in enterprises that work across multiple clouds.

- You need immediate access to new resource types or features.

- Your compliance, audit, and policy enforcement depend on native cloud controls.

- You prefer to minimize dependencies on third-party tools.

- Portability isn’t a concern; consistency and depth are.

6. Makefile: The Lightweight Automation Layer

Not every team needs a full-blown Infrastructure-as-Code engine. Sometimes, you just need a simple, reproducible way to run a series of CLI commands consistently, safely, and in CI/CD pipelines. That’s where Makefile fits in.

Make isn’t technically an IaC tool. It doesn’t maintain state, detect drift, or describe resources declaratively. Instead, it acts as a lightweight orchestrator, automating SDK or CLI commands that you’d otherwise run manually.

Automating GCP Provisioning with Make

Here’s a Makefile that authenticates with a service account and creates a Compute Engine VM:

KEY_FILE := auth.json

PROJECT_ID := my-sandbox

REGION := us-east1

VM_NAME := devcontainer-1

VM_TYPE := e2-medium

gcloud_login:

@echo "Authenticating with GCP..."

@gcloud auth activate-service-account --key-file=$(KEY_FILE)

create_vm:

@echo "Creating VM instance $(VM_NAME)..."

@gcloud compute instances create $(VM_NAME) \

--project=$(PROJECT_ID) \

--zone=$(REGION)-b \

--machine-type=$(VM_TYPE)

delete_vm:

@echo "Deleting VM instance $(VM_NAME)..."

@gcloud compute instances delete $(VM_NAME) --quiet

all: gcloud_login create_vm

Run make all to authenticate and provision the instance, or make delete_vm to tear it down. You can also integrate this directly into CI/CD pipelines or local bootstrap scripts, no dependencies beyond the CLI tools you already use.

When to Use Make Over IaC

Use Make when:

- You need a procedural, not declarative, approach.

- Your infra setup is small, dynamic, or short-lived (test clusters, sandboxes).

- You want reproducible CLI automation, not long-term state tracking.

- You already rely heavily on SDK commands (e.g., gcloud, aws, or az).

Make is not a replacement for Terraform, Pulumi, or Crossplane, but it’s often the glue around them. It orchestrates setup steps, secret injection, or CI tasks before handing off to a proper IaC pipeline.

Multi-IaC Complexity: The Hidden Challenge

Running multiple Infrastructure-as-Code tools sounds manageable until you scale with multiple microservices and teams. Terraform for networking, Pulumi for app infrastructure, Crossplane for Kubernetes, and a few leftover CloudFormation stacks remain for legacy cloud. Each tool works well alone, but together they create one of the hardest operational problems in platform engineering: fragmented state and governance.

1. Fragmented state = partial truth

Each IaC tool maintains its own understanding of reality. Terraform stores its state remotely (S3, TFC, GCS), Pulumi keeps it in Pulumi Cloud or local backends, and Crossplane tracks everything as Kubernetes CRDs. Once teams start mixing tools, you lose a single source of truth. When an incident happens, you can’t instantly answer simple questions like:

- “Who owns this subnet?”

- “Was this IAM role created by Terraform or Pulumi?”

- “Why does the actual config not match what’s in code?”

2. Drift becomes invisible

Each tool detects drift only within its own scope. Terraform can’t see console edits or Pulumi changes. Pulumi won’t know if someone used Crossplane to replace a resource. The result is silent drift, resources that no longer match any IaC definition. By the time it shows up, it’s usually during an application failure or security review.

3. Governance and compliance breakdown

Every IaC system has its own tagging, naming, and policy frameworks. Terraform may use OPA or Sentinel, Pulumi might rely on unit tests, and CloudFormation has its own Stack Policies. When these coexist, enforcing consistent policies (like mandatory encryption, region restrictions, or tag schemas) becomes nearly impossible. Audit logs live across different pipelines, and compliance teams lose the ability to trace ownership end-to-end.

4. Operational cost compounds

Each IaC tool has a separate:

- Providers and SDK versions to maintain

- State backends to secure

- CI/CD integrations to wire

- Update and deprecation cycles to track

This multiplies maintenance work across teams. A small provider version bump in Terraform might break a shared module, while Pulumi SDK updates need their own regression tests. Over time, you end up with drift not only in infrastructure, but also in how automation itself behaves.

5. Collaboration slows down

Engineers become tool-specialized: “the Terraform team,” “the Pulumi team,” “the Crossplane guys.” Cross-reviewing code across tools becomes inefficient. Context switching between HCL, Python, and YAML adds friction, and debugging multi-layered environments (where one tool’s resource depends on another’s) becomes a slow, error-prone process.

The challenge with multi-IaC environments isn’t that the tools don’t work; it’s that they don’t talk to each other. Without a unified governance layer, you end up with blind spots, policy gaps, and rising operational costs. That’s the gap modern platforms like Firefly fill, not by replacing your tools, but by making them visible, synchronized, and governable across the entire stack.

How Firefly Solves the Governance Gap

By this point, it’s clear that Terraform isn’t obsolete, but it’s also no longer the whole picture. Infrastructure teams don’t run on a single IaC tool anymore. Terraform, OpenTofu, Pulumi, Crossplane, and CloudFormation often coexist within the same organization, each serving a specific layer or team. This results in powerful automation, but fragmented visibility. You know what you deployed, but not always what’s still running, what drifted, or what’s unmanaged.

That’s where Firefly fits in, not as another Infrastructure-as-Code tool, but as the governance layer above them all.

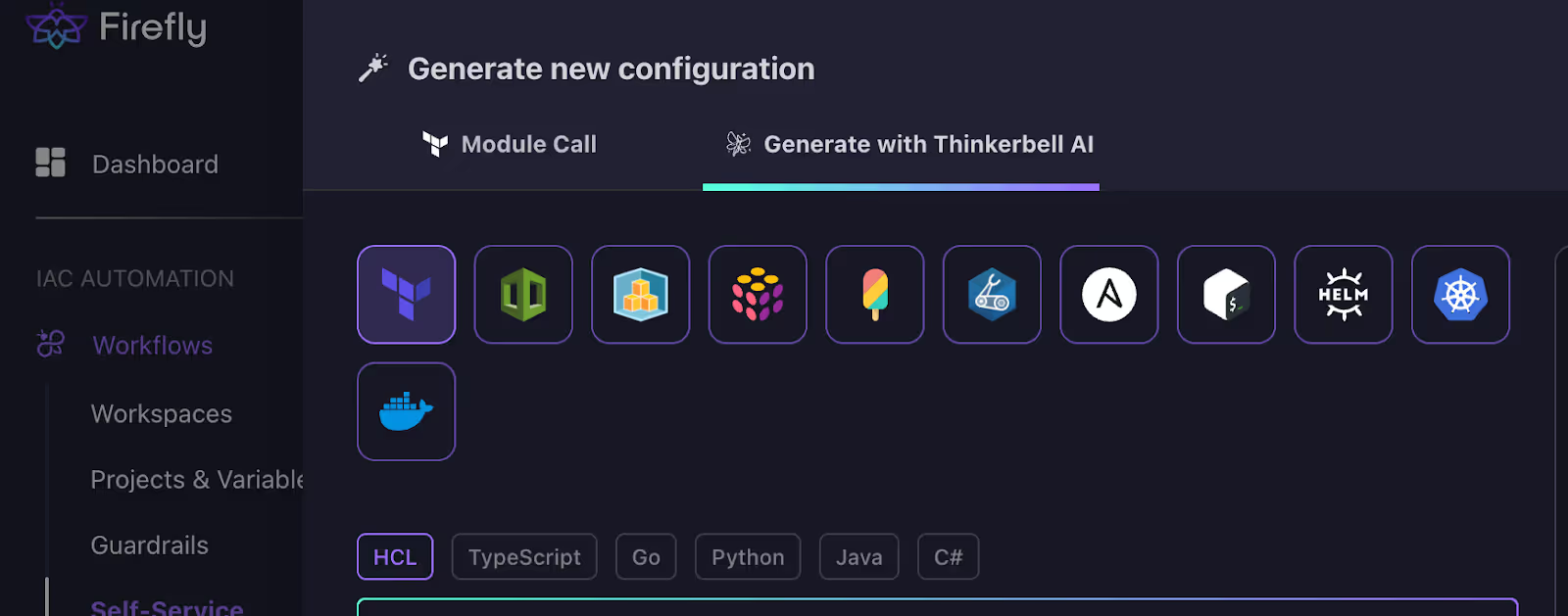

It connects directly to your cloud accounts and IaC states, unifies what’s declared with what’s deployed, and continuously tracks drift, ownership, and compliance. Instead of forcing teams to change how they provision, Firefly enhances what they already use: Terraform, OpenTofu, Pulumi, Crossplane, Bicep, and even ClickOps-created resources.

Firefly’s “Generate New Configuration” interface displays Thinkerbell AI’s capability to intelligently create IaC templates using multiple languages and frameworks, simplifying the setup process for multi-tool environments.

This view demonstrates how Firefly uses AI assistance to generate new configurations seamlessly across various IaC tools, eliminating the manual effort of initial setup.

Unified Visibility Across IaC and Cloud

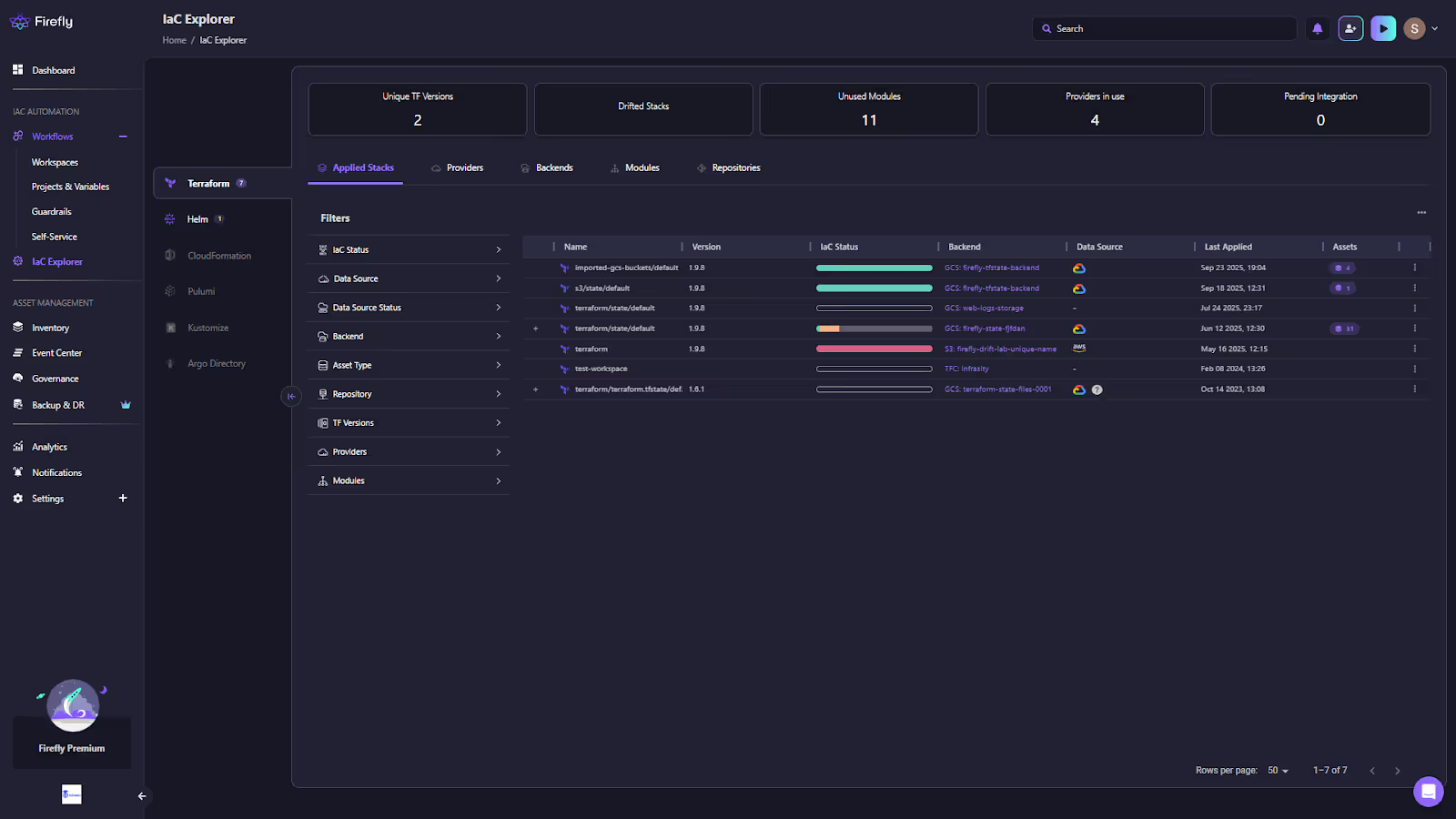

The foundation of Firefly is its IaC Explorer, with an asset inventory that merges cloud resources with IaC definitions. It scans your Terraform states, Pulumi stacks, and Crossplane manifests, then compares them to what’s live in AWS, Azure, and GCP, as shown in the snapshot below, the IaC explorer of Firefly listing all the states scanned:

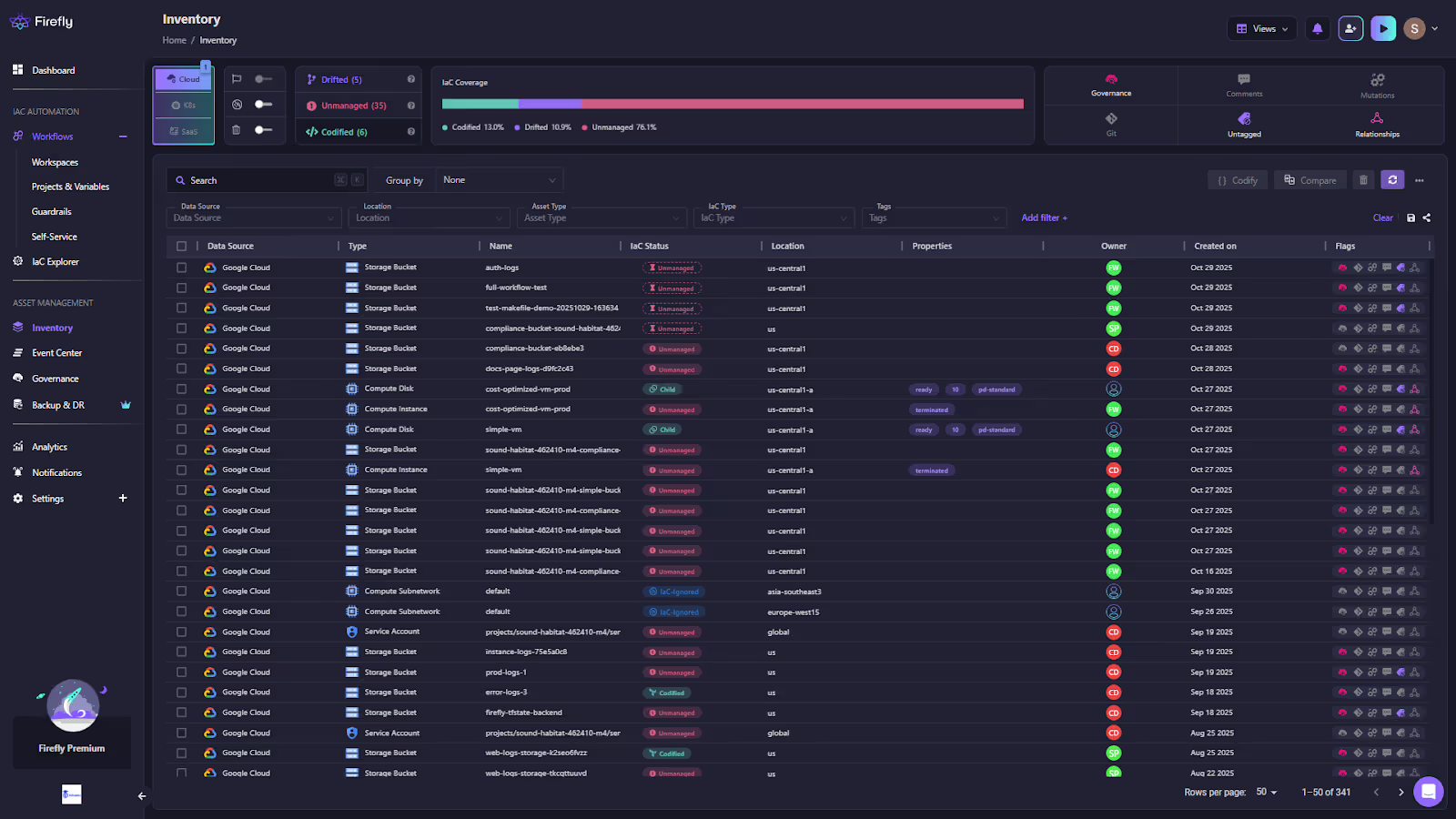

The result of this scan is a single inventory as shown in the snapshot below:

The inventory above answers to all that an enterprise wants to track, like:

- Which resources are managed by IaC

- Which have drifted from their declared state

- Which were created manually (ClickOps) and have no code source

Teams can instantly see every workspace, module, and stack, whether defined in code or not. It’s like replacing dozens of state files and spreadsheets with one live, queryable map.

FAQs

What is the AWS equivalent of Terraform?

AWS CloudFormation is the closest equivalent to Terraform. It lets you define and manage AWS infrastructure as code using YAML/JSON templates, offering deep integration with AWS services but limited multi-cloud flexibility.

What is the difference between Terraform Enterprise and Terragrunt?

Terraform Enterprise is a commercial platform offering governance, SSO, and audit features for large teams. Terragrunt is an open-source wrapper that simplifies Terraform configurations, manages dependencies, and enforces DRY principles, but doesn’t add enterprise features.

What is the difference between Terraform Enterprise and OpenTofu?

Terraform Enterprise is HashiCorp’s licensed enterprise solution with paid governance and support. OpenTofu is a fully open-source community fork of Terraform under the Linux Foundation, providing the same IaC functionality without licensing restrictions.

Is Terraform an ETL tool?

No. Terraform is an Infrastructure as Code (IaC) tool used to provision and manage cloud resources, not to extract, transform, or load data like ETL tools do.

.svg)