TL;DR

- Enterprises have large cloud footprints that were created long before Terraform; rebuilding them isn’t an option, so Terraform Import becomes essential.

- Terraform 1.5+ improves imports with declarative import blocks and automatic config generation, making the workflow easier to automate and review.

- Manual imports don’t scale well; they require perfect IDs, clean HCL, correct state handling, and careful drift checks.

- Firefly automates this end-to-end by discovering unmanaged resources, generating Terraform code, creating PRs, running imports through CI, and monitoring drift afterwards.

- Together, import blocks + Firefly provide a reliable way to bring existing AWS, Azure, and GCP resources under Terraform at scale.

Most enterprises already run cloud environments that long predate Terraform adoption. These setups usually contain years of manually created EC2 instances, VNETs, storage accounts, load balancers, and databases spread across AWS, Azure, and GCP. Turning that legacy footprint into Infrastructure as Code without rebuilding anything is where Terraform Import becomes critical.

Engineers are already automating this process. In a recent post on X (formerly Twitter), someone shared an Azure Pipeline that runs Terraform Import directly inside a CI job to sync existing Azure resources into state. It’s a good example of how teams are shifting from ad-hoc CLI imports to pipeline-driven, repeatable workflows.

This guide explains how Terraform Import works, how to apply it reliably across clouds, and how Firefly accelerates the process for large enterprise environments.

What Is Terraform Import

Most cloud environments contain resources that were created long before Terraform was introduced. Terraform Import is the mechanism that lets Terraform take ownership of those live resources without rebuilding them. It works by mapping a real cloud object to a Terraform resource address, then writing that relationship into the state file. Once the import is complete, Terraform manages the resource the same way it manages anything it creates itself.

How the original CLI import works

The classic import flow relied on the CLI command:

terraform import google_storage_bucket.db_logs db-logs-01

This updates Terraform state only. It doesn’t write the configuration. You must already have a matching resource block in your code before running this command. For one or two resources, this is manageable, but it becomes painful when you need to import dozens of buckets, VMs, or load balancers. Every ID must be correct, every address must match, and any small mismatch results in drift or import conflicts.

Import blocks: a declarative way to import

To make imports cleaner and easier to automate, Terraform introduced import blocks. Instead of running one-off CLI commands, you declare imports directly in HCL:

import {

id = "db-logs-01"

to = google_storage_bucket.db_logs

}This shifts import logic into version control, where it can be reviewed just like any other change. It also makes imports repeatable across environments instead of relying on someone’s local terminal history.

Generating configuration during import

When you run a plan with the -generate-config-out flag, Terraform reads the live resource and generates a .tf file for you. This eliminates a significant amount of manual guesswork, particularly for resources that have dozens of arguments.

Example:

terraform plan "-generate-config-out=bucket-config.tf"

Terraform examines the live bucket and writes the configuration file you’ll actually manage going forward. You don’t need to create the directory manually if you provide a direct file path.

Importing a GCS Bucket into Terraform

Here’s a real example that shows the entire workflow end-to-end.

Start with a minimal setup by setting up a provider:

terraform {

required_providers {

google = {

source = "hashicorp/google"

version = "~> 5.0"

}

}

}

provider "google" {

project = "project-id-xxxxxx-XX"

region = "us-central1"

}Terraform needs this to authenticate against your project and look up the live bucket.

Declare the import in code

import {

id = "db-logs-01"

to = google_storage_bucket.db_logs

}The id is the exact bucket name as it appears in GCP.

Run Terraform with config generation enabled,

terraform plan "-generate-config-out=bucket-config.tf"

Terraform reads the bucket from GCP and generates a complete .tf file containing the required arguments and structure.

Review the generated configuration

Terraform produces a clean resource block that looks like this:

resource "google_storage_bucket" "db_logs" {

default_event_based_hold = false

enable_object_retention = false

force_destroy = false

labels = {}

location = "US"

name = "db-logs-01"

project = "sound-habitat-462410-m4"

public_access_prevention = "enforced"

requester_pays = false

rpo = "DEFAULT"

storage_class = "STANDARD"

uniform_bucket_level_access = true

soft_delete_policy {

retention_duration_seconds = 604800

}

}Terraform automatically omits read-only fields and computed metadata. What you get is a usable starting point that reflects the actual bucket running in production.

Move the file into your normal module structure

Place bucket-config.tf in the same location as your storage resource management code in your codebase. Adjust naming and labels if needed.

Remove the import block and apply

Once the resource is imported and the configuration has been cleaned up, delete the import block so that Terraform doesn’t attempt to import it again.

Then run:

terraform applyTerraform should show no changes, which confirms the imported resource now matches your configuration exactly.

Why Enterprises Need Terraform Import for Existing Cloud Infrastructure

Most enterprises already run cloud environments that were built long before Terraform was adopted. These environments often contain business-critical workload, such as databases, networks, storage systems, and compute resources, that cannot be recreated or interrupted. Terraform Import gives organisations a safe way to bring that existing footprint under Infrastructure as Code without touching production.

1. Avoid downtime and resource rebuilds

The biggest benefit of import is avoiding resource recreation since rebuilding a production database, an internal load balancer, or a shared VPC is not practical for any enterprise. Import lets Terraform take ownership of those resources in place without changing behaviour or causing downtime.

2. A path to IaC adoption

Teams often inherit cloud resources built manually through consoles, scripts, or legacy automation. Import provides a clean, incremental way to convert these environments into Terraform, one service, one module, or one subsystem at a time, without any disruptive migrations.

3. Unified and consistent management

After import, every resource is managed through the same Terraform workflow. This removes configuration drift and makes the Terraform state file the single source of truth for the entire environment, regardless of the age of the resource.

4. Better team collaboration

Imported resources become part of the same version-controlled codebase as everything else. Engineers work from a common state, follow consistent CI/CD processes, and review changes through pull requests instead of running isolated manual actions.

5. Stronger security and compliance

Once legacy resources are managed under Terraform, policy-as-code tools can automatically validate every change. Security teams gain full visibility and an auditable history of all infrastructure changes, providing a far better alternative to relying on console activity logs or undocumented manual tweaks.

6. Disaster recovery and refactoring support

If a Terraform state file is lost or damaged, import allows teams to rebuild the state from live cloud objects. It’s equally useful when refactoring: you can safely remap resources to new module paths or restructure code without touching the resources themselves.

7. Modern import features for enterprise adoption

Terraform 1.5+ introduced import blocks and config generation, making the import workflow far more automation-friendly. Teams can declare imports in code, run them through CI/CD, and let Terraform generate accurate HCL. This is a major improvement for large-scale imports and aligns well with enterprise-grade workflows.

In short, Terraform Import gives enterprises a reliable way to bring existing cloud resources under IaC management without touching what’s already running.

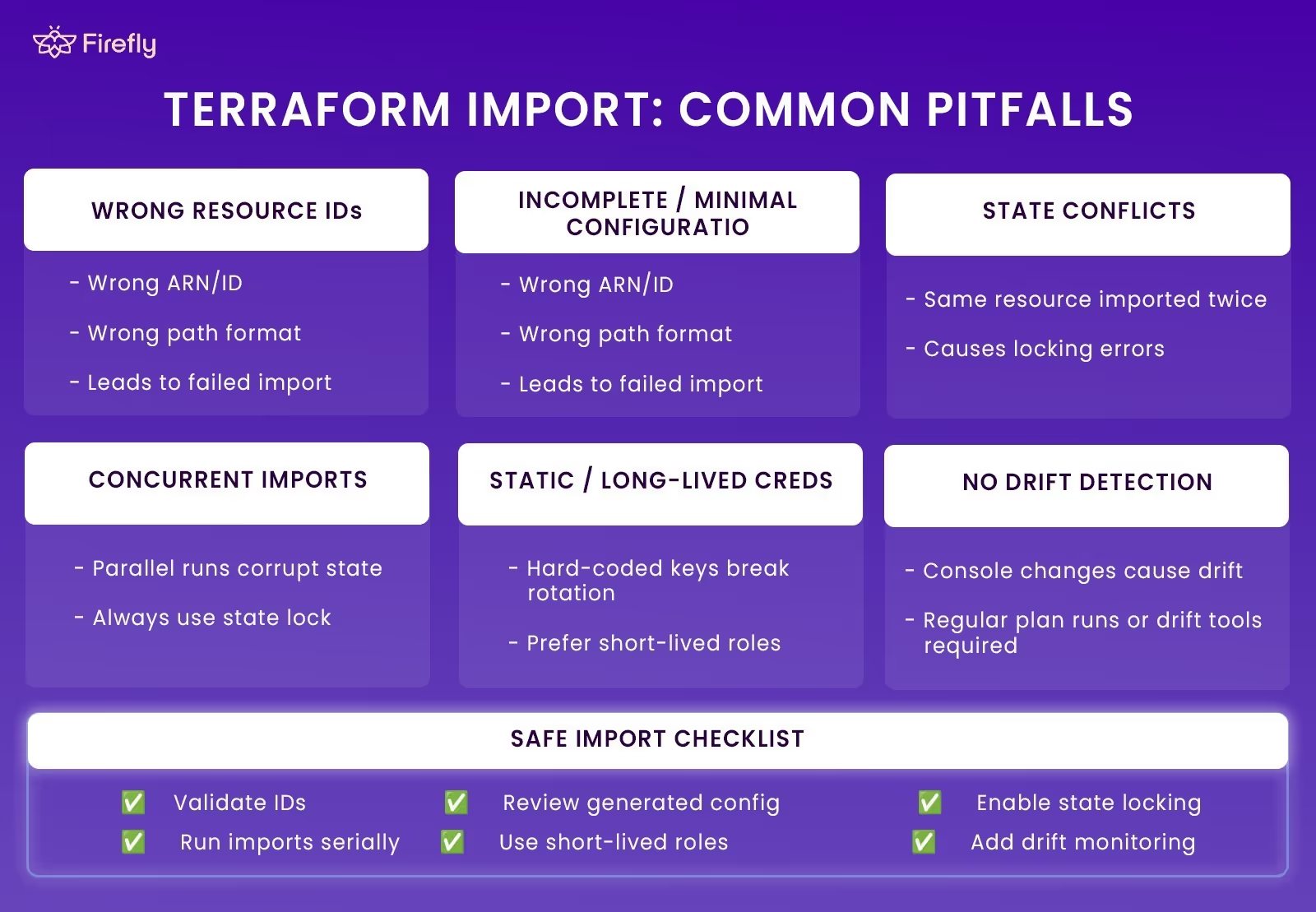

Terraform Import: Common Pitfalls

Importing existing cloud resources into Terraform is straightforward in small environments, but at enterprise scale, the process becomes more sensitive. Multiple teams, shared accounts, and mixed workflows increase the chances of mistakes that can affect state accuracy or cause unintended configuration changes. These are the pitfalls that show up most often.

Key Pitfalls to Watch For

- Wrong Resource IDs: Each cloud uses different ID formats (ARNs in AWS, full resource paths in Azure, names or numeric IDs in GCP). Using the wrong one leads to failed or incorrect imports.

- Incomplete or Minimal Configuration: Missing required arguments after import can cause Terraform to modify the resource on the next apply. Generated configuration should always be reviewed and cleaned up.

- State Conflicts: Importing the same resource into multiple states or addresses creates immediate conflict errors. Remote backends with locking prevent these collisions.

- Concurrent Imports: Running imports in parallel without proper locking can corrupt state files. Imports should run one at a time or through a dedicated CI workflow.

- Static or Long-Lived Credentials: Imports depend on live API calls. Hard-coded credentials cause rotation issues and increase operational risk. Short-lived roles or workload identity are safer.

- No Drift Detection: Imported resources can drift when changed in the console. Regular plan checks or automated drift tools are required to keep Terraform aligned with the real environment.

With the right guardrails, state locking, correct IDs, clean configuration, and drift checks, imports become a stable, repeatable part of the workflow instead of a risky one-off task.

Enterprise Use Cases

Enterprises adopt Terraform Import for a wide range of real-world situations where rebuilding or re-provisioning infrastructure simply isn’t an option. Many organisations have years of workloads running across AWS, Azure, and GCP, and import provides a clean path to bring everything under Infrastructure as Code without outages or disruptive migrations.

1. Legacy cloud onboarding

Older environments often contain manually created VMs, storage accounts, network components, and databases. Import lets teams bring this legacy footprint under Terraform without changing or restarting any workloads.

2. Multi-cloud centralisation

Enterprises running across AWS, Azure, and GCP can unify all infrastructure into a single Terraform workflow. Import gives every cloud, regardless of how or when it was provisioned, the same lifecycle and governance model.

3. Mergers and acquisitions

Acquired environments often arrive unmanaged and undocumented. Import allows teams to integrate acquired cloud assets into their existing Terraform infrastructure while maintaining production systems intact.

4. Audit and compliance alignment

Once a resource is imported, all future changes pass through version control and CI/CD. This brings legacy resources under the same compliance, approval, and policy-as-code checks as newly created infrastructure.

5. State recovery and refactoring

When teams lose state files or restructure modules, import becomes the only reliable way to reconnect Terraform to the real infrastructure. It lets teams reorganise code or rebuild state safely.

How Firefly Simplifies Terraform Import

When you’re trying to import existing cloud resources at scale, the hard part isn’t the terraform import command; it’s everything around it: finding what exists, validating resource types, generating clean HCL, running imports safely through CI, and keeping everything aligned across multiple teams and cloud accounts.

That’s the workflow Firefly streamlines.

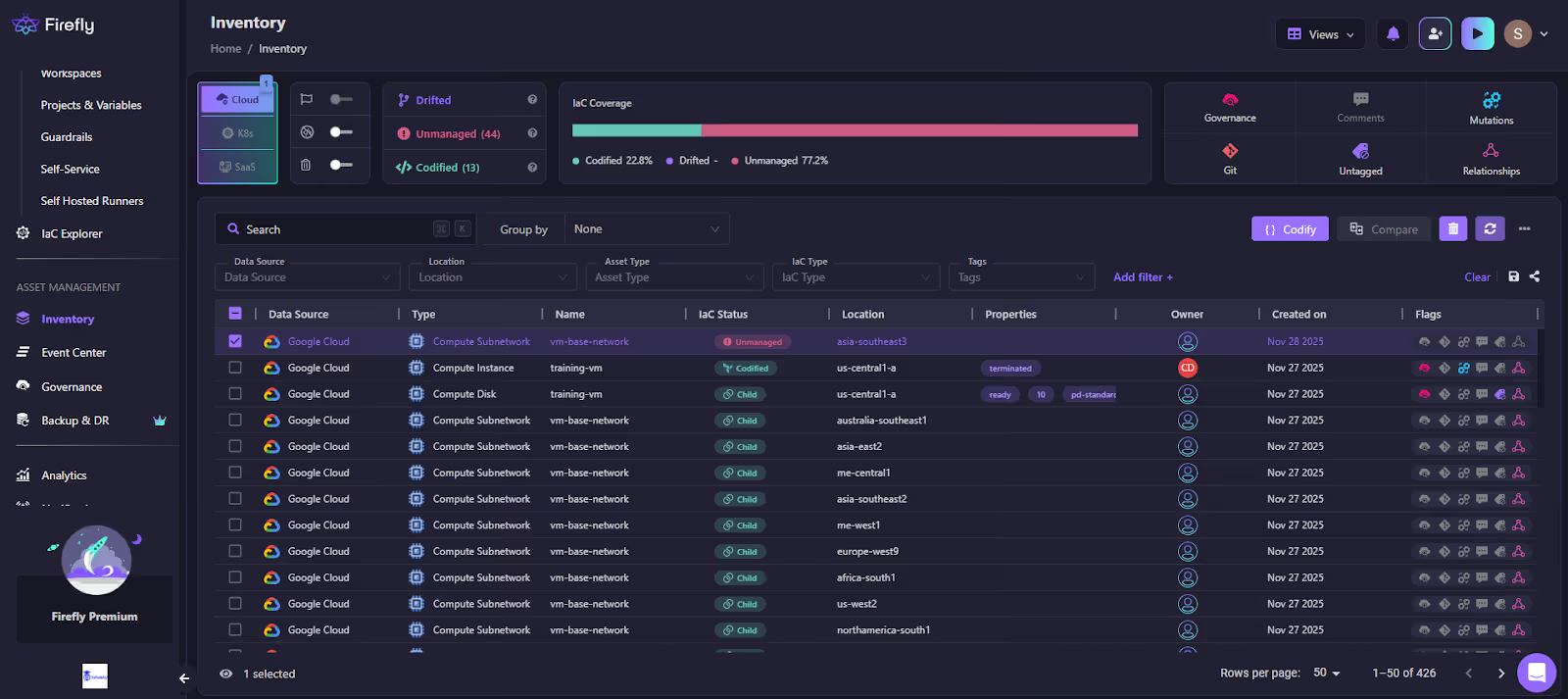

Here’s how Firefly handles Terraform imports in practice, as shown in the workflow below:

Explanation of the workflow

1) Inventory and classification

Firefly builds an inventory by querying AWS, Azure, and GCP APIs directly. Every resource is automatically classified as:

- Codified (already managed by Terraform)

- Unmanaged (exists in cloud but not in Terraform)

- Drifted (in Terraform, but cloud state changed)

- Ghost (in Terraform state/config, but missing in cloud)

This view serves as the baseline when a team needs to decide what to import, what to refactor, and what requires attention. Terraform alone doesn’t provide this visibility.

2) Selecting resources and generating Terraform code

From the Inventory screen, you can multi-select unmanaged resources, EC2 instances, storage buckets, load balancers, IAM roles, and anything Firefly detected.

When you click Codify, Firefly generates:

- the correct Terraform resource type

- a complete, schema-aligned HCL block

- An import mapping that ties the cloud ID to your resource address

- provider requirements if needed

The output is deterministic and follows the provider schema. You still review it and edit it before committing, but the heavy lifting, discovering IDs, choosing resource types, and matching attributes, is handled for you.

3) Pull request generation and Terraform execution

Firefly opens a pull request with the generated Terraform files to a VCS(GitHub, GitLab, Bitbucket, etc.) of your choice. From there, the import runs through your existing CI or a Firefly Runner. That runner then:

- initialises the workspace

- generates the plan

- performs the import

- applies the updated configuration

Everything happens against the same backend, credentials, and variables used by the environment’s normal Terraform pipelines. That removes the biggest source of import failures: inconsistent local setups.

4) Policy checks and compliance guardrails

While the PR is open, Firefly runs policy-as-code checks to ensure the imported resources meet organisational standards, tags, encryption settings, network rules, and so on. This is especially useful for older resources that were created manually.

5) Drift monitoring after the import

Once imported, Firefly continuously checks each resource for drift. If anything changes outside Terraform, console updates, scripts, or another tool, Firefly detects it and can automatically generate a remediation PR.

This closes the loop. The resource remains under Terraform control after the initial import, preventing it from drifting out of sync again.

FAQs

What is the difference between terraform mv and terraform import?

terraform mv is used when a resource is already managed by Terraform, and you want to rename it or move it to a new module path. It only updates the state file.

terraform import is used to bring an existing cloud resource (created outside Terraform) into Terraform’s state so Terraform can manage it.

What is the difference between the import command and the import block in Terraform?

The terraform import command is a manual operation. You run it once, it updates the state, and it requires you to already have a valid resource block in your configuration.

Import blocks are declarative. You write them in HCL, store them in version control, and run them through normal plan/apply. With Terraform 1.5+, you can also generate configuration from these blocks using -generate-config-out.

Is Terraform import safe?

Import itself is safe; it doesn’t modify or recreate the resource. It only records the mapping in the state file. The risk comes after the import: if your configuration doesn’t match the live resource, Terraform may try to change or recreate parts of it during the next apply. This is why reviewing generated HCL, backing up the state, and using remote state with locking are essential parts of a safe import workflow.

What are the limitations of Terraform import?

Terraform Import has several limitations. It only updates the state and won’t generate a configuration unless you use Terraform 1.5+ with -generate-config-out. Some provider resources don’t support import, and any generated HCL still needs cleanup. If the configuration doesn’t match the live resource, Terraform may show drift or propose unwanted changes. Manual imports also don’t scale well in large environments, and importing the same resource into multiple states will lead to conflicts.

.svg)