Terraform holds 34.28% of the configuration management market, and for most engineering teams, it’s the default way to define and roll out cloud infrastructure across AWS, GCP, Azure, and Kubernetes. But in real enterprise environments, Terraform rarely covers everything. Large portions of production, built years ago through consoles, CLIs, or older automation, sit outside code, creating a mixed estate with both managed and unmanaged resources.

When only “new” infrastructure is in Terraform, you lose IaC’s core benefits: auditability, drift detection, consistency, and predictable deployments. The real requirement for true IaC is simple: every resource must be codified, in state, and reproducible from code alone.

The biggest blocker is imports. Traditional terraform import is slow, manual, and doesn’t generate configuration, making it nearly impossible to codify existing environments at scale. This post breaks down where Terraform workflows start failing in large estates and how modern import workflows, including Terraform Import Blocks and automated tooling, finally make full codification realistic.

Quick Overview: Terraform for Engineers Who’ve Skipped It

Terraform works on a simple principle: define the infrastructure you want in code, and let the tool handle the API calls to build or update it. Everything is written in HCL, which is easy to read and keeps the workflow consistent across platforms. The provider system is what makes Terraform practical in real environments. AWS, GCP, Azure, Kubernetes, Cloudflare, Datadog, GitHub, and many others expose their APIs through Terraform providers. This consistency matters most in companies running services across multiple clouds and regions, where having one workflow for everything reduces a lot of operational overhead.

The core workflow stays the same everywhere:

- terraform init prepares the working directory and downloads provider plugins

- terraform plan shows the exact diff between what’s in code and what currently exists

- terraform apply makes the changes

- State tracks the resources Terraform manages, so updates and deletions happen correctly

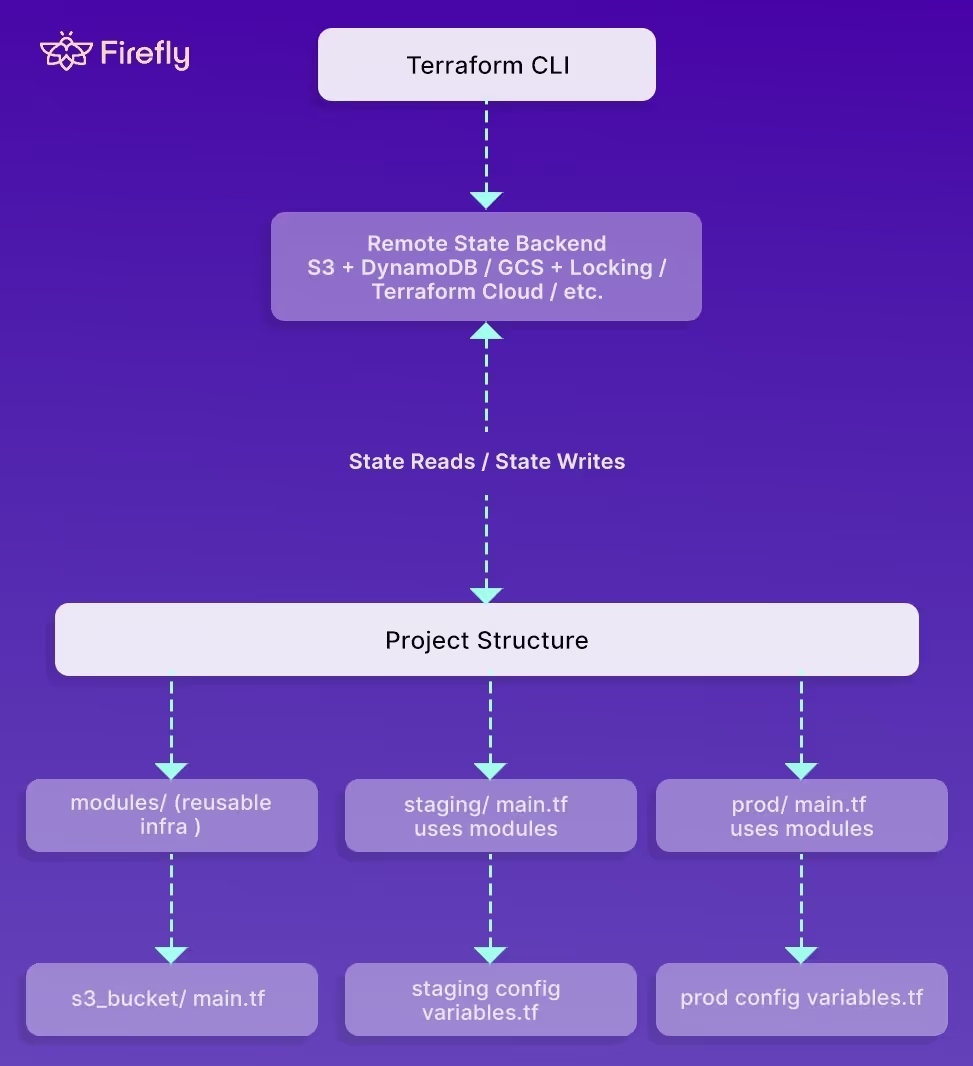

The state is where most of the hidden complexity lives. Teams running multiple environments: dev, staging, prod, and sometimes multiple prod regions, need a stable backend. S3 with DynamoDB, GCS with locking, Terraform Cloud, etc., all exist to avoid situations where two engineers run Terraform at the same time and corrupt the state. Local state works for learning, not for shared environments.

As visible in the layout below:

Modules are the other building block, since they wrap a piece of infrastructure into something reusable: a VPC, an S3 bucket, an EKS cluster, or a database. Good module design keeps inputs minimal, avoids exposing internal details, and gives every environment the same implementation without copy-pasting files.

A typical layout looks like this:

infra/

├── modules/

│ └── s3_bucket/

│ └── main.tf

├── prod/

│ └── main.tf

└── staging/

└── main.tf

The module defines the resources, and each environment folder calls that module with its own inputs, keeping staging, production, and regional accounts consistent. This pattern holds up in single-account setups with small state files, but problems surface as Terraform use spreads across teams and accounts: state locking slows work, shared components like VPCs or IAM roles don’t map cleanly to per-environment folders, and cross-account dependencies become difficult to coordinate. The next section explores these issues in detail.

What Goes Wrong When Terraform Grows Beyond a Single Team

Terraform works smoothly when one team owns a small set of resources in a single account. The moment multiple teams start managing VPCs, IAM, networking, application stacks, and shared services across several accounts or projects, the weak points show up quickly. The issues aren’t theoretical; they happen in every large environment.

State Becomes a Central Failure Point

The state file grows as more resources are added. Networking, IAM, compute, storage, everything ends up in a shared backend. When multiple pipelines push changes to the same layer, locking delays, partial writes, and blocked applies start appearing. A broken state backend can stop all deployments until someone fixes it.

Drift Appears Faster Than It Can Be Tracked

Incidents, console updates, one-off fixes, and older automation all introduce drift. Terraform won’t catch any of it unless someone manually runs a plan. By the time drift is noticed, the diff is usually large and unclear, and teams aren’t sure whether applying it will overwrite something important.

Different Teams Run Terraform in Different Ways

In growing organisations, Terraform gets executed from several places, CI pipelines, internal tooling, and scheduled jobs, all with slightly different behaviours. Without a single plan/apply workflow, changes become hard to trace, and the same layer of infrastructure ends up being managed in inconsistent ways.

Cross-Account Dependencies Break Easily

Shared networking, IAM trust relationships, central logging, or encryption keys all span multiple accounts. Terraform doesn’t coordinate these boundaries natively. If one team updates a shared service without sequencing their change against dependent accounts, things break.

Common Anti-Patterns Make Everything Worse

A few patterns always cause trouble in multi-team setups:

- Hardcoded values

- No remote backend or incomplete locking

- State edited by hand

- Modules with no versioning

- Multiple automation paths writing to the same state

- Huge root modules managing unrelated components

None of these causes immediate failures in small environments, but they become constant sources of friction once several teams share the same infrastructure layers.

Patterns That Make Terraform Production-Ready

Once Terraform is used across multiple teams and accounts, the configuration, state layout, and deployment process need to be structured deliberately. These patterns consistently keep Terraform reliable in larger environments where infrastructure changes every day and multiple pipelines apply changes concurrently.

Remote State Strategy

Remote state is the backbone of any multi-team Terraform setup. It keeps the state consistent and prevents parallel operations from corrupting it.

Typical setups look like this:

- AWS: S3 bucket for the state file, DynamoDB table for locking

- GCP: GCS bucket for the state file, optional lock table or object versioning

- Vault / Consul: Native backends when teams already use HashiCorp tooling

A production-ready backend has:

- Encryption at rest

- Versioning or snapshots for state recovery

- Explicit state separation per environment or per infrastructure layer

- Mandatory locking to avoid overlapping applies

- Clear ownership of each state file so updates don’t collide

This avoids the most common failure patterns: blocked pipelines, partial writes, and inconsistent state across teams.

Module Design & Governance

Modules are effectively the API surface for infrastructure. With several teams consuming them, the design and versioning of these modules matter as much as the resources they create.

A strong module design approach includes:

- Expose only inputs that should vary across environments, such as CIDR ranges, instance sizes, names, timeouts, or retention settings. Keep internal values (IAM policies, logging configuration, tagging structure) inside the module.

- Hide implementation details. A caller should not need to know the internals of how subnets, IAM roles, or monitoring resources are built.

- Use a private module registry so modules are versioned, reviewed, and released like software.

- Follow clear versioning rules. Breaking changes require a major version bump; new capabilities require a minor; internal refactors remain patch versions.

- Keep modules focused. A module should represent one infrastructure component: VPC, ALB, EKS node group, RDS instance, etc. Splitting responsibilities keeps the blast radius small and updates manageable.

This keeps infrastructure consistent across accounts and reduces the risk of changes leaking into production unexpectedly.

Multi-Account / Multi-Project Setup

Most organisations run multiple cloud accounts or projects: production, staging, development, shared services, security, data, and so on. Terraform needs a layout that matches that structure.

A reliable multi-account setup usually includes:

- Landing zone or baseline configuration for each new account, networking defaults, IAM boundaries, logging destinations, guardrails

- Bootstrap modules to create foundational resources before any application modules run

- Organisation-wide tagging is enforced through modules or policies, not left to each team to remember

- Dedicated CI roles for each account, so automated applies run with scoped permissions

- Separation of root modules per account or per layer, so a change in one area doesn’t impact unrelated resources

This layout keeps state isolated, reduces blast radius, and makes dependencies across accounts predictable.

Common Use Cases in Modern Infra Teams

Terraform is used across a wide range of infrastructure stacks today. The patterns vary, but the goals are the same: consistent environments, predictable changes, and infrastructure that can be reproduced across accounts and regions. These are the use cases that show up most often in real environments.

AI/ML Infrastructure

Modern ML workloads depend on a mix of high-cost and tightly controlled resources, GPU instances, managed training services, model endpoints, feature stores, and storage layers. Terraform helps teams standardise these pieces across environments.

Typical components managed with Terraform:

- GPU node groups or dedicated GPU instance pools

- AWS SageMaker training jobs and endpoints

- GCP Vertex AI models, endpoints, and private service connections

- AWS Bedrock foundation model integrations

- Supporting resources: S3/GCS buckets, IAM roles, network isolation, logging

These environments change often, especially during experimentation. Terraform modules maintain stability while allowing teams to adjust parameters such as instance size, model version, and autoscaling thresholds without rebuilding everything manually.

Kubernetes Infrastructure

Most teams use Terraform not to manage Kubernetes workloads, but to create and maintain the underlying cluster infrastructure.

Common patterns include:

- Provisioning EKS, GKE, or AKS clusters

- Managing node groups and autoscaling groups

- Configuring VPCs, subnets, and load balancers used by clusters

- Wiring cluster authentication and IAM/OIDC roles

- Managing supporting services like NAT gateways, ALBs, and network security

Terraform provides consistent cluster creation across accounts and regions, which is critical when teams maintain multiple clusters for dev, staging, and production.

Internal Platform Engineering

Platform teams often expose Terraform modules to developers through a self-service layer. Instead of asking teams to write Terraform directly, they provide a catalogue of pre-approved infrastructure templates.

Typical setup:

- Modules define the actual infrastructure (databases, caches, buckets, queues, services).

- A platform UI or service (Backstage, Port, internal tooling) collects inputs.

- The platform generates a Git PR containing the module call.

- CI runs Terraform plan, review, and apply.

This gives developers a simple workflow while keeping Terraform usage standardised. It prevents one-off patterns and ensures that every environment, regardless of who requested it, follows the same module design, tagging, IAM policies, and networking rules.

Handling the Gaps Terraform Doesn’t Cover: Drift, Secrets, and Cost Controls

Terraform manages resource creation and updates based on what’s defined in the configuration and stored in the state. What it doesn’t do is track everything that happens to those resources after they’re deployed. Cloud platforms allow direct edits through their consoles, APIs, and other automation. Those changes don’t pass through Terraform, and nothing updates the configuration or the state automatically. Over time, this creates mismatches in configuration, data exposure risks, and cost behaviour that the Terraform workflow isn’t aware of.

Drift Detection and Remediation

Drift appears whenever the live configuration in AWS, GCP, or Azure no longer matches what Terraform expects. Terraform can detect this through terraform plan, but only when someone runs it. Most teams rely on external tooling to make this reliable.

A common tool for this is driftctl, which compares cloud APIs with your Terraform state and flags unmanaged or drifted resources.

Example usage:

# Scan using local state

driftctl scan

# Equivalent

driftctl scan --from tfstate://terraform.tfstate

# Specify AWS credentials

AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=XXX AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=XXX driftctl scan

# or use a named profile

AWS_PROFILE=profile_name driftctl scan

# Scan against an S3 backend state file

driftctl scan --from tfstate+s3://my-bucket/path/to/state.tfstate

# Scan multiple state files

driftctl scan --from tfstate://terraform_S3.tfstate --from tfstate://terraform_VPC.tfstate

# Use glob patterns for state files

driftctl scan --from tfstate://path/to/**/*.tfstate

driftctl scan --from tfstate+s3://path/to/**/*.tfstateThe workflow for handling drift is always the same: detect the change, decide whether it was intentional, update the Terraform configuration if needed, and re-apply so state and infrastructure match again.

Secrets Management

Terraform doesn’t manage secrets; it only passes them through. If teams aren’t careful, sensitive values end up in places they shouldn’t: state files, CI logs, or even Git. This happens often when someone hardcodes credentials into variables or forgets to mark outputs as sensitive.

Most mature setups use dedicated secret systems:

- Vault for dynamic credentials or short-lived tokens

- AWS Secrets Manager, Azure Key Vault, or GCP Secret Manager for cloud-native storage

- SOPS when secrets must exist in Git but need to be encrypted with KMS or GPG

A few guardrails make this reliable: encrypt state in the backend, keep secrets out of .tfvars in Git, mark sensitive outputs correctly, and ensure plan logs in CI don’t leak secret values. These basics prevent credentials from spreading across systems where they don’t belong.

Cost Controls and Budget Guardrails

Terraform has no awareness of the impact on cloud costs. Changes to instance types, node pools, storage classes, or retention settings can increase spend significantly without warning. Teams typically integrate cost tooling into their IaC pipeline.

Common approaches include:

- Cloud-native cost dashboards (AWS Cost Explorer, Azure Cost Management, GCP Billing)

- FinOps platforms for multi-cloud visibility, like Firefly

- Policy-as-code tools (OPA, Sentinel) to block expensive or unapproved resource types

These checks help catch cost increases before they reach production.

Validating Terraform Plans in CI Using OPA

Teams that rely on Terraform for day-to-day changes eventually need a consistent way to check those changes before anything is applied. Simply because different engineers touch the same cloud accounts, and it’s too easy for a misconfigured bucket or VM to slip through. Terraform itself won’t tell you whether a change violates an internal requirement; it just evaluates configuration and state. The guardrails usually live in CI.

Here’s a GCP example that mirrors what many teams do:

Terraform generates a plan, the plan is exported to JSON, OPA evaluates it, and CI decides whether the change can proceed. Nothing complicated, ust the kind of lightweight validation pipeline that holds up well as usage grows.

Terraform Configuration

The bucket is intentionally misconfigured so the OPA policy has something real to catch. The compute instance is a typical “safe default” setup.

resource "google_storage_bucket" "bucket" {

name = var.bucket_name

location = "US"

uniform_bucket_level_access = false # intentionally out of policy

}

resource "google_compute_instance" "vm" {

name = var.instance_name

machine_type = "e2-micro"

zone = var.zone

scheduling {

preemptible = true

automatic_restart = false

}

boot_disk {

initialize_params {

image = "ubuntu-os-cloud/ubuntu-2004-lts"

size = 10

}

}

network_interface {

network = "default"

# intentionally no external IP

}

}The point isn’t the infrastructure; it’s how the plan is evaluated.

OPA Policies

OPA reads the JSON plan and evaluates it against your rules. In this example:

- The bucket policy actually enforces something.

- The compute policy is a scaffold that shows how rules evolve over time.

GCS Bucket Policy

Blocks any bucket that disables uniform bucket-level access.

package terraform.gcs

deny[msg] {

input.planned_values.root_module.resources[_].type == "google_storage_bucket"

resource := input.planned_values.root_module.resources[_]

resource.values.uniform_bucket_level_access == false

msg := sprintf(

"Bucket '%s' has uniform_bucket_level_access = false. It must be true.",

[resource.values.name]

)

}

policy_summary = {

"total_violations": count(deny),

"compliant": count(deny) == 0,

"violations": deny,

}

Compute Policy

A minimal structure with disabled rules, exactly how teams introduce new policies without breaking existing workflows.

package terraform.compute

deny[msg] {

false # rule intentionally disabled

msg := "disabled"

}

warn[msg] {

false

msg := "disabled"

}

policy_summary = {

"total_violations": count(deny),

"total_warnings": count(warn),

"compliant": count(deny) == 0,

"violations": deny,

"warnings": warn,

}

GitHub Actions Workflow

The pipeline runs Terraform, evaluates the plan with OPA, and makes a simple yes/no decision. Here are the key sections, exactly the way someone would wire this up in their environment.

Storage Policy Validation

opa eval \

-d policy/storagepolicy.rego \

-i tfplan.json \

"data.terraform.gcs.policy_summary" > storage_policy_result.json

VIOLATIONS=$(jq -r '.result[0].expressions[0].value.total_violations' storage_policy_result.json)

if [ "$VIOLATIONS" -gt 0 ]; then

echo "Storage policy failed"

exit 1

fiCompute Policy Validation

opa eval \

-d policy/computepolicy.rego \

-i tfplan.json \

"data.terraform.compute.policy_summary" > compute_policy_result.json

COMPLIANT=$(jq -r '.result[0].expressions[0].value.compliant' compute_policy_result.json)

if [ "$COMPLIANT" != "true" ]; then

echo "❌ Compute policy failed"

exit 1

fiCombined Gate

if [ "$STORAGE_COMPLIANT" == "true" ] && [ "$COMPUTE_COMPLIANT" == "true" ]; then

echo "All checks passed"

else

echo "Blocking deployment"

exit 1

fiThe entire pipeline hinges on one thing: the plan must pass the policy evaluation before Terraform can apply, with no manual review required.

This setup gives teams a check to decide whether a change is acceptable before Terraform applies anything. It keeps the apply step clean, prevents obvious mistakes from reaching production, and doesn’t depend on engineers remembering internal rules buried in documentation. It’s intentionally small, but the structure is identical to what teams use for larger environments.

How Firefly Complements Terraform

By this point in the blog, it’s clear Terraform works best when two things are true:

- everything is expressed as code, and

- that code stays aligned and versioned with what’s actually running.

Most organisations never reach that state. They inherit accounts full of existing resources, multiple teams touch the same environments, and plenty of infrastructure is created outside of Terraform. The more the footprint grows, the harder it becomes to trust plans, reason about drift, and keep code current.

Firefly focuses on the parts of the Terraform workflow that are hardest to operate at scale and automates the work that normally burns the most engineering time.

Codifying Existing Infrastructure (with Import Blocks + Ready Terraform)

The biggest slowdown in maturing an IaC practice is onboarding existing resources into Terraform. Manually writing config and stitching together terraform import commands doesn’t scale when there are hundreds or thousands of resources already running.

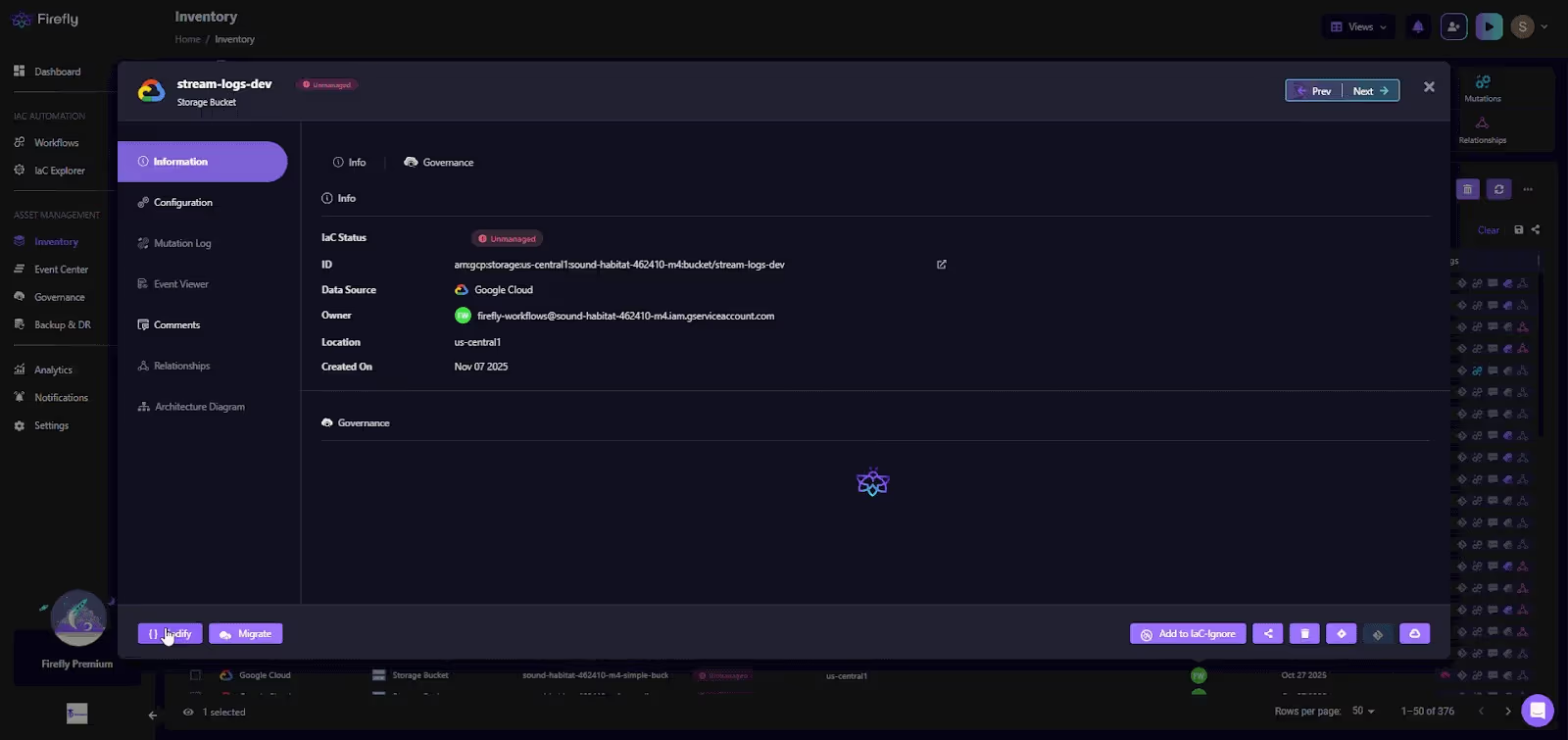

In the flow below:

Firefly solves this directly:

- It scans cloud accounts and identifies anything Terraform doesn't manage.

- It generates Terraform-ready configuration for those resources.

- It generates import blocks for each resource, so you can adopt them cleanly without recreating or destroying.

- It opens PRs with the generated code if you want to codify through GitOps.

This is the fastest way to move large, brownfield environments toward full IaC coverage without infrastructure rebuilds or risky hand-written imports.

Continuous Drift Detection with Context That Matters

Terraform only sees drift when someone runs a plan, and even then, the diff rarely tells you which module, which stack, or which team owns the resource. In larger orgs, that uncertainty alone is enough to stop engineers from clicking “apply.”

Firefly continuously inspects cloud resources, compares them against their Terraform definitions, and shows:

- Exactly what changed,

- where it diverges from the IaC,

- and the specific Terraform update required to realign them.

Instead of a vague plan diff, you get a structured explanation tied directly to the original configuration. This lets teams fix drift confidently instead of guessing what the “correct” state should be.

Stack Awareness and State Visibility Across Accounts

One of Terraform’s blind spots is understanding how code, state files, and cloud resources relate across many accounts and teams. In real environments, it’s normal to have:

- multiple backends,

- fragmented state files,

- orphaned modules,

- Resources that no one is sure belong to Terraform or not.

Firefly maps every resource to the Terraform stack (or module) that manages it. It also surfaces:

- which backend/state file manages it,

- when it was last applied,

- whether it drifts,

- and whether it’s covered by IaC at all.

This gives platform teams the visibility Terraform doesn’t natively provide.

Policy Enforcement Beyond the Terraform Plan

OPA in CI is useful, but it only sees what the Terraform plan contains. Anything created outside Terraform, a bucket created in the console, an IAM tweak during an incident, or older resources that were never codified, will slip right past it. Most teams hit this gap early once multiple groups share the same cloud environment.

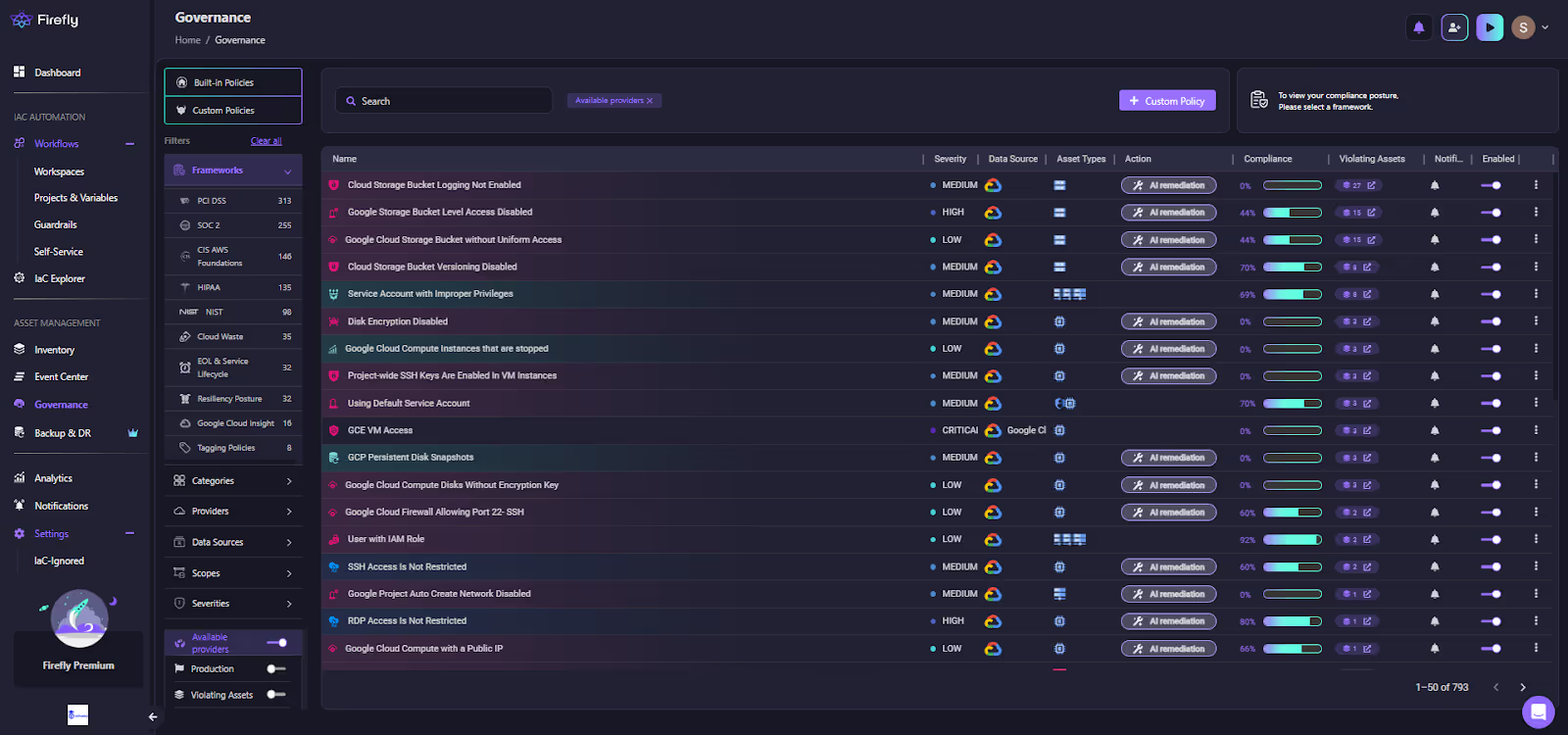

Firefly covers both sides: governance on the live environment and guardrails on Terraform plans.

Live Governance Across All Cloud Resources

Firefly continuously evaluates the real environment against built-in and custom rules, not just the resources already in Terraform. This includes access controls, encryption settings, default service accounts, firewall rules, unencrypted disks, and dozens of similar checks across your cloud footprint.

The governance view makes this obvious at a glance: which policies fail, how severe they are, and which assets are out of line.

This solves the gap CI can’t touch: everything that exists or changes outside Terraform.

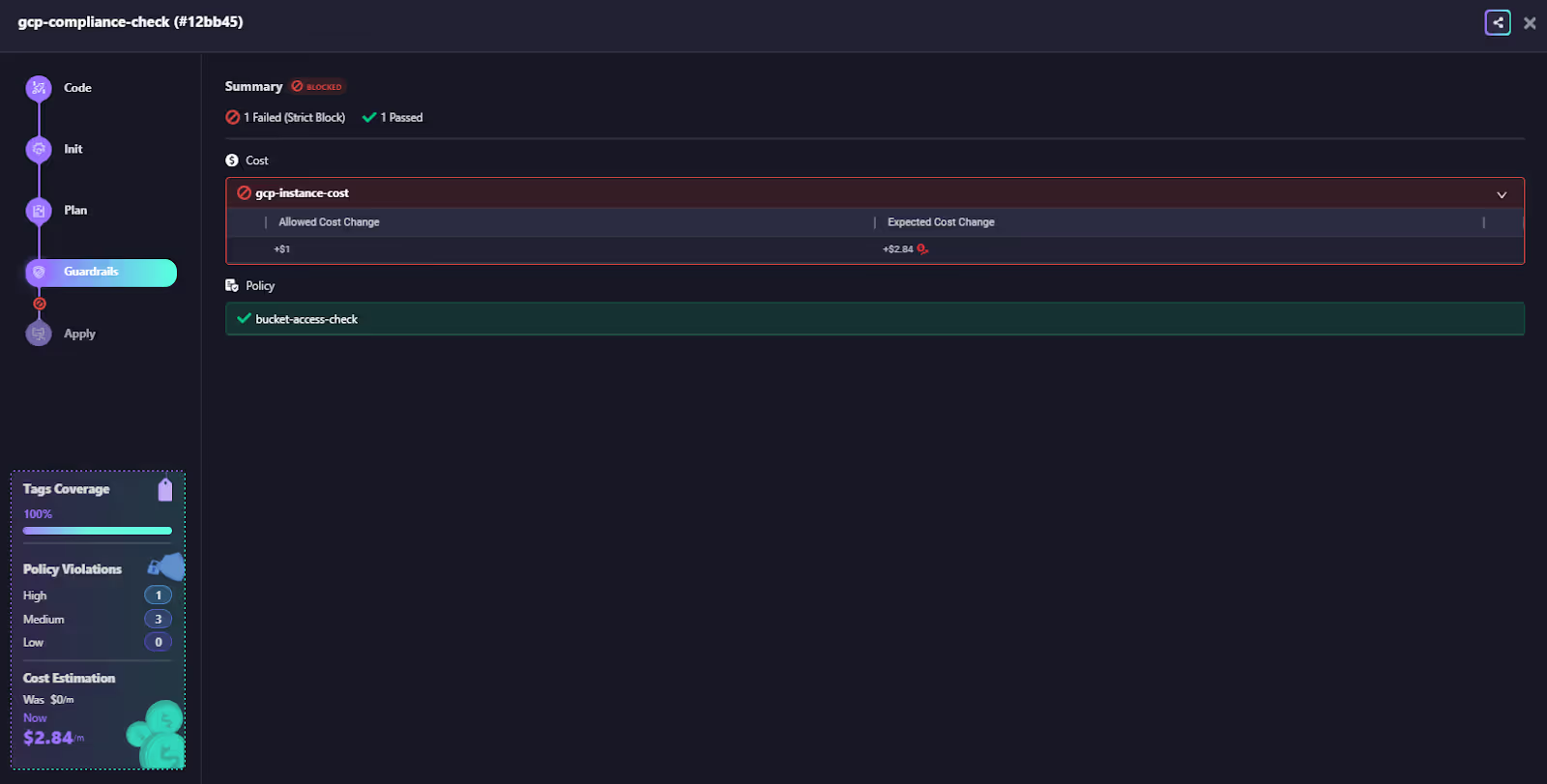

Blocking Unsafe Terraform Plans Before Apply

When Terraform runs inside a Firefly workspace, the plan is evaluated against guardrails before apply. If the change violates cost boundaries, tagging rules, access settings, or any other guardrail, the run is blocked with a clear explanation.

This gives teams consistent plan-time enforcement without building and maintaining dozens of custom Rego files, and without expanding CI pipelines every time a new resource type needs a check. You don’t need to write and maintain separate Rego policies for every resource type. Firefly ships with a large set of built-in policies in the governance dashboard and custom guardrails with cost, security and policy checks.

FAQs

What is the difference between Terraform and other IaC?

Terraform is a declarative, stateful IaC tool that keeps a central state file and manages infra through a plan, apply workflow. Tools like CloudFormation/Bicep are cloud-native, Pulumi uses real programming languages, and Ansible is procedural. Terraform stands out for its provider ecosystem, dependency graph, and predictable lifecycle management.

Is Terraform the best IaC?

Terraform is one of the strongest general-purpose IaC tools especially for multi-cloud, modularity, and strong lifecycle control. But “best” depends on needs: single-cloud teams may prefer native tools, dev-heavy teams may prefer Pulumi, and Kubernetes shops might choose Crossplane. It’s excellent, not universally optimal.

Does Ansible count as IaC?

Ansible can provision infrastructure, but it’s primarily a configuration management and orchestration tool. It runs tasks procedurally, doesn’t maintain a state file, and lacks Terraform-style planning. It supports IaC patterns, but it’s not a pure infrastructure-lifecycle tool.

What is the difference between Ansible and Terraform for IaC?

Terraform manages the complete lifecycle of cloud resources using a declarative model and a state file. Ansible runs procedural tasks, making it ideal for OS/app configuration and orchestration. Terraform is for provisioning and lifecycle, Ansible is for configuration and operations, and they’re often used together.

What are the best Terraform Cloud alternatives?

The best Terraform Cloud alternatives include Firefly, Spacelift, env0, Scalr, Pulumi Cloud, and CI/CD-based setups like GitHub Actions or GitLab CI. These tools offer different strengths such as better cost predictability, multi-IaC support, stronger governance, or deeper CI/CD integration making them good choices depending on whether you want a fully managed control plane or more flexibility and control over your infrastructure workflows.

.svg)