TL; DR

- Terraform Stacks introduce a native deployment and orchestration layer that addresses enterprise issues such as workspace sprawl, manual run sequencing, and fragile CI-driven Terraform execution.

- Infrastructure is defined as reusable components (networking, compute, databases, etc.) and instantiated through deployments that control where and how often those components run across regions, accounts, and environments, with an isolated state per deployment.

- Stacks automatically manage dependency ordering, centralize provider configuration and authentication, and support controlled promotion flows (dev, staging, prod), removing the need for custom orchestration logic.

- Stacks run exclusively on HCP Terraform, enabling built-in approvals, execution control, and secure identity handling (for example, OIDC with short-lived, ephemeral tokens), but introducing platform lock-in, limits, and a steeper learning and debugging curve.

- To operate stacks effectively at scale, an external visibility and governance layer such as Firefly is needed to provide cross-stack visibility, drift detection beyond Terraform state, policy enforcement, and inventory and cleanup insights.

Once Terraform usage spreads across multiple teams, regions, and accounts, the weak spots become obvious: too many workspaces, no consistent run order, and constant manual sequencing whenever one part of the depends on another. A small change to a shared VPC or a cluster module often means updating dozens of workspaces in the correct order, and Terraform itself has no awareness of those cross-workspace dependencies.

A recent Reddit post from a developer captured this problem well. They liked the structure that Stacks introduced, cleaner state boundaries, and a predictable layout, but were uneasy about the lock-in that comes with tying their entire IaC model to Terraform Cloud or Enterprise. That hesitation is common when teams start evaluating how to scale Terraform beyond a handful of environments.

The appeal of Stacks is that they add a deployment layer that Terraform has always left to custom scripts and CI pipelines. Components such as networking, clusters, and application infrastructure are defined once, and Stacks handle how they’re instantiated across regions and environments. If an app depends on a Kubernetes cluster that doesn’t exist yet, Stacks understands that relationship and creates the cluster component first. This was the same scenario demonstrated in Armon Dadgar’s keynote, preventing failed runs caused by missing upstream infrastructure.

By giving Terraform a higher-level deployment graph, Stacks make it far easier to roll out consistent environments at scale. The rest of this blog looks at how they solve these enterprise challenges and how platforms like Firefly fill the remaining gaps around visibility, drift, governance, and multi-cloud control.

What Terraform Stacks Are

Terraform Stacks provide a structured way to define infrastructure once and deploy it repeatedly across environments without duplicating modules or wiring dozens of workspaces together. Instead of treating each environment as a separate Terraform entry point, stacks introduce a clear separation between infrastructure definition and deployment targets.

You describe what infrastructure should exist using components, and you describe where and how many times it should run using deployments. Terraform then handles execution order, dependency sequencing, and state isolation between the two.

- Components define the building blocks: networking, clusters, databases, or shared platform services.

- Deployments define the instances: which accounts, regions, or environments those components are applied to.

This model removes the need to copy Terraform code per environment or maintain custom CI logic just to control run order.

Components: Defining Infrastructure Building Blocks

A stack is built from components, each defined in a tfcomponent.hcl file. A component wraps a standard Terraform module and describes how that module should be instantiated. The module itself remains unchanged and contains normal Terraform resources, variables, and outputs.

For example, a VPC component might look like this:

component "vpc" {

source = "./modules/vpc"

for_each = var.regions

inputs = {

name = "stack-vpc-${each.value}"

}

providers = {

aws = provider.aws.this[each.value]

}

}This does three things:

- It points to a normal Terraform module (./modules/vpc)

- It allows the module to be instantiated once per region

- It explicitly maps the provider instance that the module should use

By keeping components focused and single-purpose, dependencies between them remain easy to understand and safe to change.

Deployments: Turning Components into Environments

Components define structure, but deployments define execution. Deployments are declared in a tfdeploy.hcl file and represent concrete instances of the stack.

deployment "staging" {

inputs = {

regions = ["us-east-1", "us-west-2"]

role_arn = "arn:aws:iam::123456789012:role/stack-deployer"

}

}Each deployment:

- Produces its own Terraform state

- Uses the same component definitions

- Is isolated from other deployments like prod or dev

This replaces the common pattern of one directory or workspace per environment while preserving strict separation between environments.

Provider Configuration at the Stack Level

Stacks also centralize provider configuration and authentication. Providers are declared at the stack level and passed into components explicitly.

provider "aws" "this" {

for_each = var.regions

region = each.value

assume_role {

role_arn = var.role_arn

}

}This avoids repeating credential logic across modules and environments. Provider behavior, regions, assume roles, and tagging are defined once and reused consistently across all deployments.

Orchestration and Promotion Flow

Stacks include built-in orchestration. Dependencies between components are declared explicitly, and Terraform enforces execution order automatically. If computing depends on networking, networking is applied first.

Stacks also support deployment groups and promotion paths, allowing changes to move from dev to staging to production in a controlled sequence. Approval logic and rollout behavior live alongside the infrastructure definition instead of being embedded in CI scripts. Without stacks, teams usually scale Terraform by splitting infrastructure into separate directories, creating many workspaces, and relying on CI pipelines to enforce run order. That orchestration lives outside Terraform and becomes harder to maintain as platforms grow.

Stacks move this responsibility into Terraform itself. Dependencies are explicit, deployments are isolated by design, and rollouts follow a defined execution graph instead of custom scripting.

The next section walks through a hands-on example using Terraform Stacks on GCP. It shows how this model works in practice, using OIDC and Workload Identity Federation for authentication, with no service account keys or long-lived credentials, and highlights the stack-specific behaviors that matter when running Terraform at scale.

Running a Terraform Stack on GCP with OIDC Workload Identity

This example uses Google Cloud and deliberately avoids service account keys, JSON credentials, or local environment variables. Authentication is handled entirely through OIDC and short-lived tokens issued by HCP Terraform.

The objective is straightforward: define a stack once, connect it to HCP Terraform, and let HCP handle identity, execution order, and deployment lifecycle in a way that is secure and repeatable.

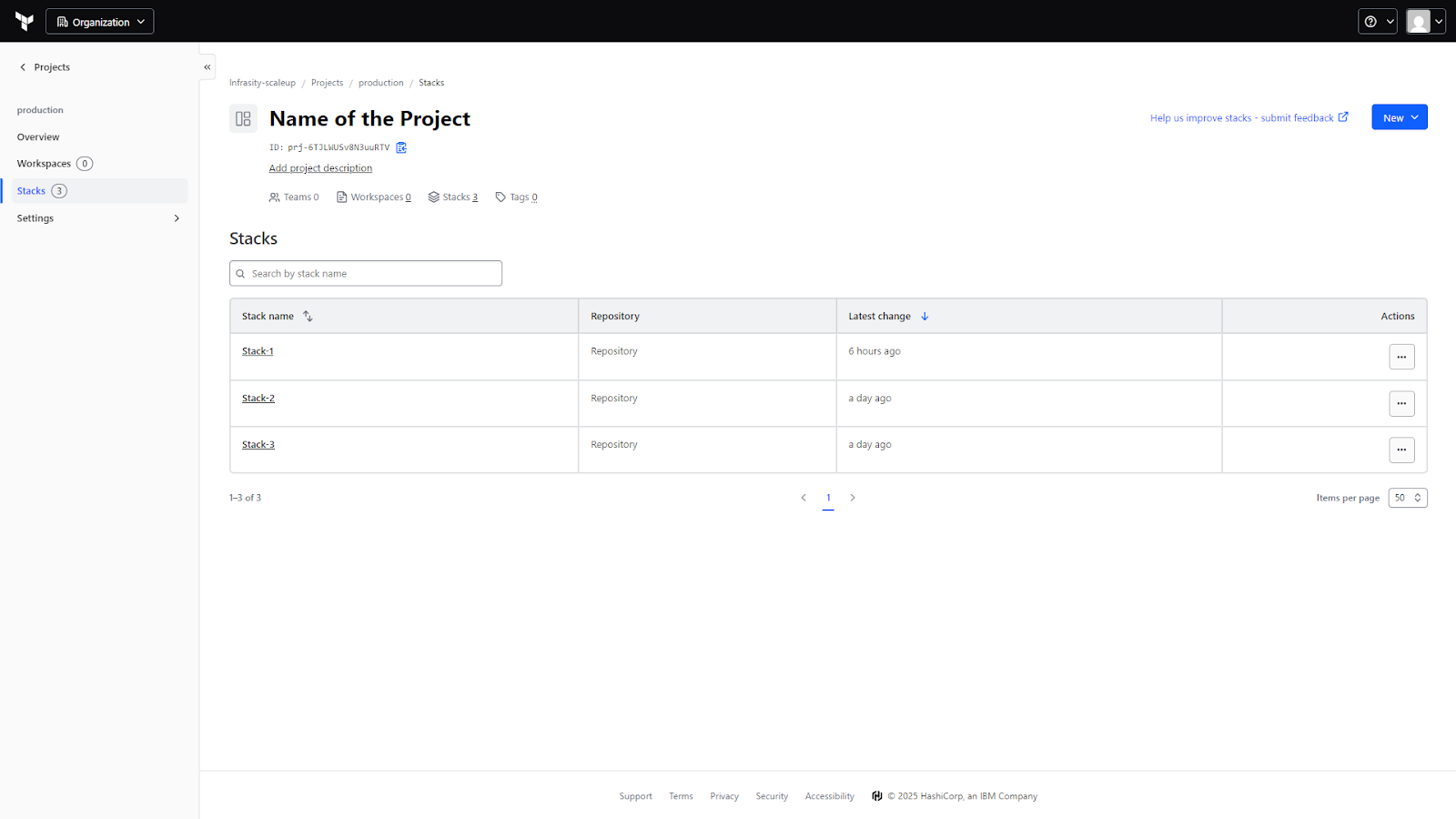

Pushing the stack and creating it in HCP Terraform

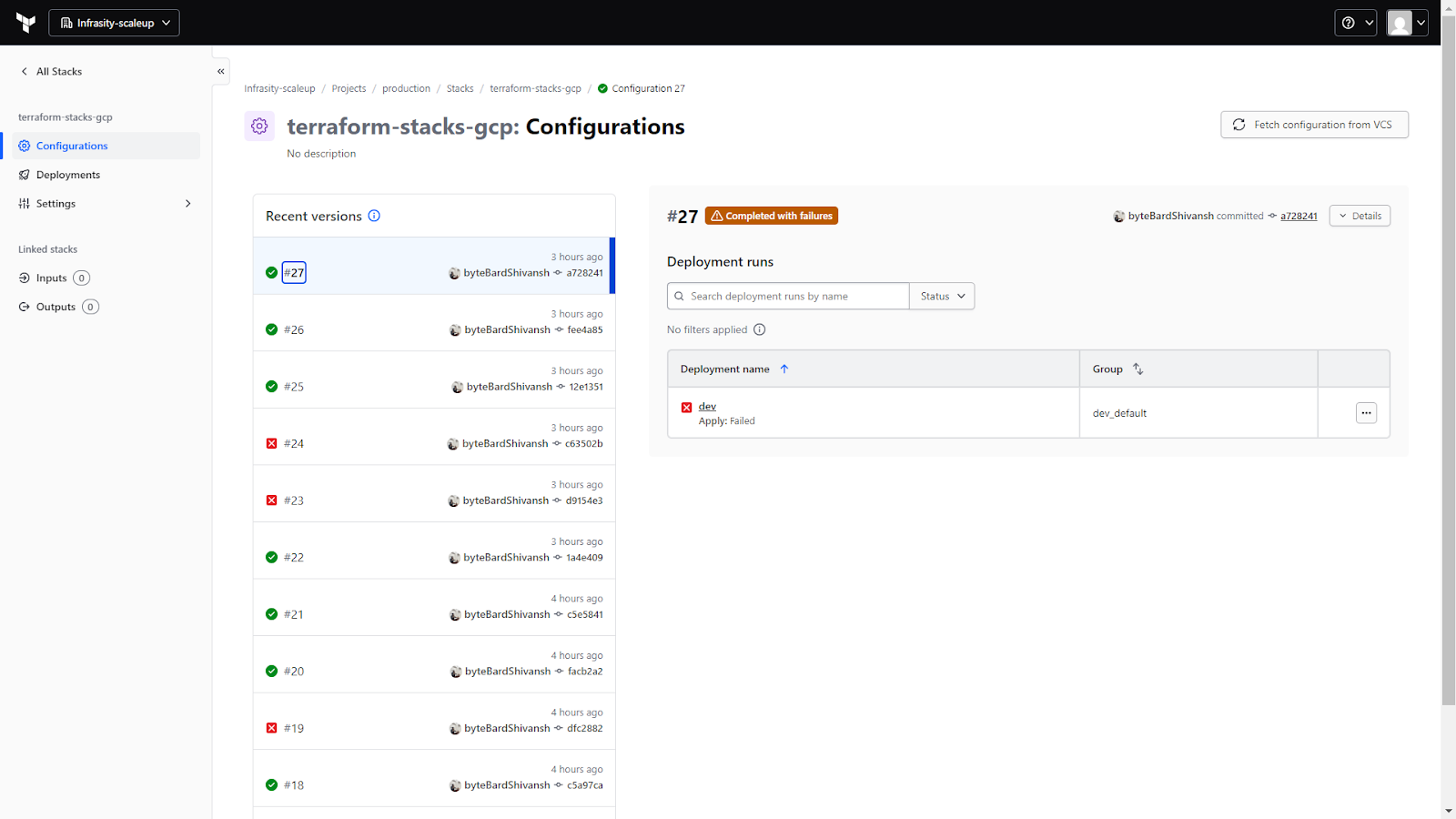

The repository contains the stack definition (tfcomponent.hcl, tfdeploy.hcl) and a simple VM module under components/vm. Once this repository is pushed to GitHub, a new stack is created in HCP Terraform and linked directly to that repo and branch. The stack name matches the repository name (terraform-stacks-gcp) to keep the mapping obvious.

From this point on, HCP Terraform becomes the execution engine. Every commit produces a new configuration version. A configuration version is HCP’s snapshot of the stack definition at a point in time, and it is what drives planning and applying deployments.

This screen is the first place to check after pushing code. It confirms that HCP is successfully pulling the stack configuration from VCS and evaluating it. Each configuration version is tied to a commit, making it easy to track what changed and when.

Why authentication must be explicit with stacks

Terraform Stacks do not inherit local credentials. There is no implicit trust in environment variables, no ADC fallback, and no access to developer machines. Everything needed to authenticate must be declared as part of the stack itself.

For GCP, this setup uses Workload Identity Federation with OIDC:

- HCP Terraform mints a short-lived OIDC JWT with the audience hcp.workload.identity

- That JWT is exchanged with Google STS

- Google uses the IAM Credentials API to mint an access token

- The access token is used to call GCP APIs

At no point are service account keys created or stored. Tokens are short-lived and exist only for the duration of the run.

Modeling identity as stack inputs

Because identity is part of execution, it is modeled as stack input. The most important variable here is the OIDC token itself:

variable "identity_token" {

type = string

sensitive = true

ephemeral = true

}Marking this variable as ephemeral is critical. It ensures the token:

- never appears in plans,

- never ends up in state,

- and is discarded after the run completes.

Other inputs define the GCP project, regions, service account, and—most importantly—the Workload Identity Provider resource name, which is used during token exchange with Google.

Provider configuration at the stack level

The Google provider is configured using external_credentials. This is done at the stack level so every component uses the same authentication model:

provider "google" "regional" {

for_each = var.regions

config {

project = var.project_id

region = each.value

external_credentials {

audience = var.sts_audience

service_account_email = var.service_account_email

identity_token = var.identity_token

}

}

}There are two different audiences, and confusing them is the most common cause of failure:

- hcp.workload.identity: Used when HCP Terraform mints the OIDC JWT.

- projects/PROJECT_NUMBER/.../providers/PROVIDER: The full Workload Identity Provider resource name. This must be used as the audience for Google STS.

They serve different purposes and must never be reused interchangeably.

Defining the component and deployment

The stack contains a single component that wraps a VM module. The component is instantiated once per region:

component "vm" {

source = "./components/vm"

for_each = var.regions

providers = {

google = provider.google.regional[each.key]

}

inputs = {

region = each.key

}

}The deployment defines where this component runs and injects the identity token:

identity_token "gcp" {

audience = ["hcp.workload.identity"]

}

deployment "dev" {

inputs = {

identity_token = identity_token.gcp.jwt

sts_audience = "projects/.../providers/terraform-hcp-provider"

service_account_email = "svc-account@project.iam.gserviceaccount.com"

project_id = "project-id"

regions = ["us-central1"]

}

}Each deployment produces its own Terraform state and is managed independently by HCP. Adding a prod deployment later would reuse the same component definition with different inputs.

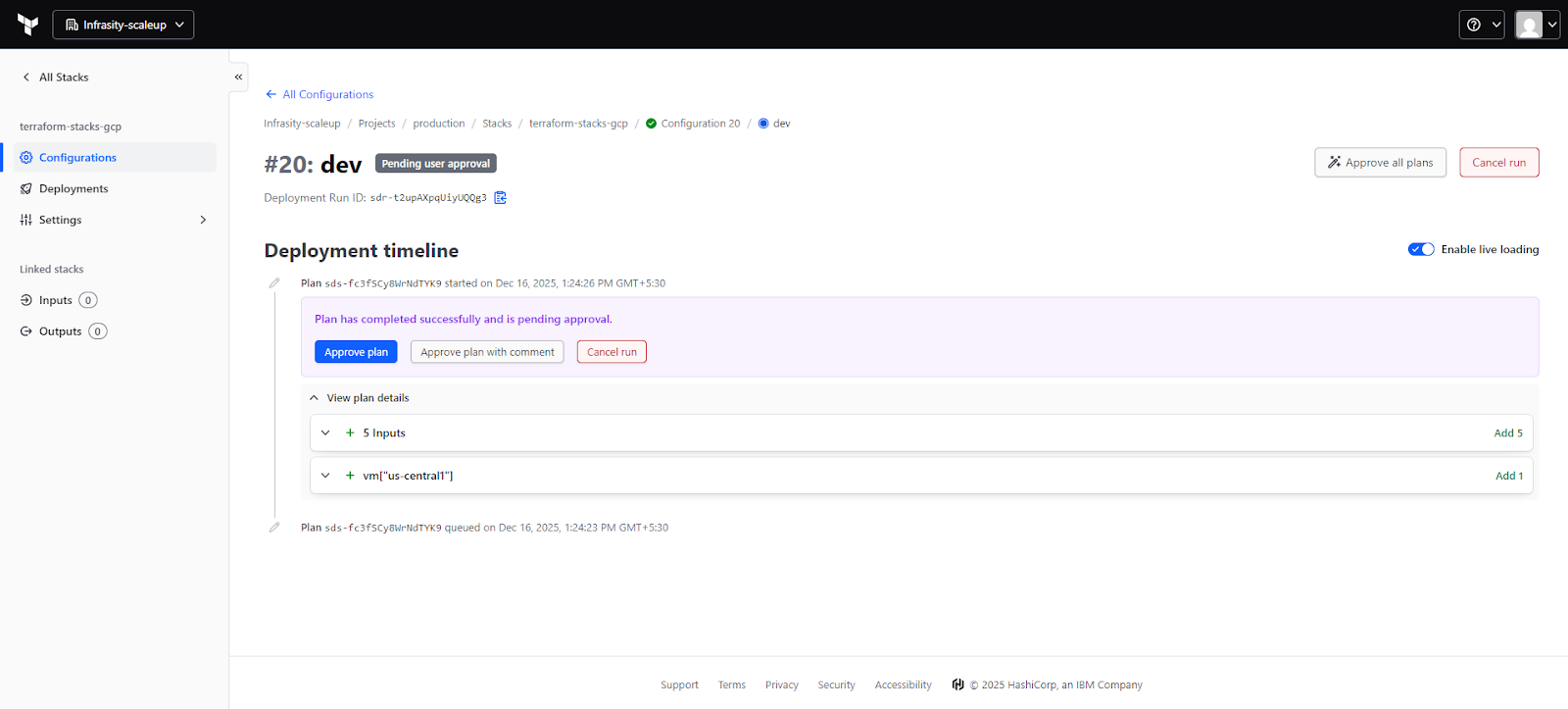

Planning, approval, and apply

Once the deployment configuration is committed, HCP Terraform automatically queues a plan for the dev deployment. The plan runs using the short-lived identity token and evaluates the component graph.

This view shows the deployment run lifecycle: plan start, plan completion, and (if configured) a manual approval gate before apply. Inputs can be inspected, resource changes reviewed, and logs checked before approving the run. The approval step is especially useful when the same stack is deployed across multiple environments.

This example shows how Terraform Stacks behave in a real cloud environment:

- Infrastructure is defined once and deployed through explicit deployments

- Authentication is part of the stack model, not an external assumption

- No long-lived secrets are created or stored

- HCP Terraform handles execution, state isolation, and approvals

Most importantly, the stack remains readable. Components describe infrastructure. Deployments describe environments. Identity and orchestration are visible, explicit, and auditable. That clarity is what makes Terraform Stacks usable at scale, beyond simple demos.

Where Terraform Stacks Fit in the Terraform Execution Model

Stacks don't introduce new resource primitives or change how modules are written. Instead, they add a deployment and orchestration layer that addresses limitations found in other infrastructure-as-code approaches. While Terraform alternatives like Pulumi, CloudFormation, or Ansible exist, Stacks enhance the native Terraform execution model by providing orchestration and dependency management that most IaC tools lack at scale.

Modules

Modules are reusable code blocks, but have no sense of lifecycle. Stacks sit above them and determine when each component runs and in what order. This lets stacks enforce dependency flow, for example, networking before compute, compute before namespaces, and namespaces before application workloads.

Workspaces

Workspaces isolate state but don’t coordinate with each other. If one workspace depends on another, you handle that manually. With stacks, deployments still have an isolated state, but the orchestration happens at the stack layer, and dependencies are explicitly defined.

Traditional Terraform CLI

Multi-directory automation with plain Terraform usually relies on custom scripts or home-grown tooling. Stacks remove that overhead. You define components once, define deployments once, and the stack engine handles layout, sequencing, and variable propagation.

Stack Architecture: Components and Deployments

A Terraform stack defines a single structure that is expanded into multiple deployments at runtime. Instead of running as one Terraform execution, the stack is evaluated by HCP Terraform, components are expanded, and each deployment is executed independently with its own state. Here’s how Terraform Stack forms a simple hierarchy: a single stack definition at the top, functional components beneath it, and multiple deployments per environment or region.

A stack commonly groups infrastructure into functional components, such as:

- Networking: VPCs, subnets, routing

- Compute: EKS, ECS, VM scale sets

- Databases: RDS, Aurora, Cloud SQL

- Platform services: IAM roles, namespaces, mesh configuration

From this single definition, deployments are created for each target environment, for example:

- production / us-east-1

- staging / us-east-1

- production / eu-central-1

Each deployment runs with its own isolated Terraform state, while the dependency order between components is enforced automatically by the stack engine. Stacks can also reference upstream or downstream stacks to consume shared outputs. This works well for larger platforms, but stack links are limited, so cross-stack relationships should be designed intentionally.

Platform Limits and Design Considerations

Stacks have practical constraints that influence how you structure them:

- Up to 20 deployments per stack

- up to 100 components

- up to 10,000 resources

- limits on stack links and exposed values

Large environments often split stacks by domain (network, platform, compute) or by region to stay within these limits while keeping the model clean.

HCP Terraform Runtime Dependency

Stacks run exclusively in HCP Terraform. Their orchestration engine, provider handling, and state operations rely on the HCP runtime. Stacks can coexist with legacy workspaces, but adopting them is also a commitment to this execution model, which is an important architectural factor.

Why Enterprises Use Terraform Stacks

Multi-Environment Infrastructure Replication

Most enterprise platforms run the same infrastructure footprint across multiple regions or accounts, VPCs, clusters, databases, shared services, and application scaffolding. With classic Terraform, each environment ends up as a separate workspace or directory, and keeping them consistent becomes a constant effort.

Stacks solve this by defining components once and generating deployments for each target environment. If you need the same baseline in four regions and three accounts, the stack produces twelve deployments with consistent structure, variables, and dependency order. A global rollout, patching network rules, updating a cluster version, or adjusting shared IAM policies can move through all environments in a controlled sequence instead of touching each workspace manually.

Full-Stack Application Deployments

Platform teams often have an infrastructure chain that includes networking, Kubernetes clusters, namespaces, service meshes, databases, and application-level resources. Managing all of this through separate workspaces creates gaps; one workspace doesn’t know if another has finished, and applications frequently depend on upstream components that haven’t been provisioned yet.

Stacks model this entire chain as a set of components with defined relationships. Networking runs first, compute layers next, then namespaces and application services. Each environment gets a fully orchestrated deployment that mirrors the intended layout. This prevents common errors like attempting to deploy workloads to a cluster or namespace that hasn’t been created yet.

Dependency Orchestration for Complex Platforms

Large organizations often maintain shared modules used by dozens of teams. When a module changes, like a VPC baseline or cluster configuration, rolling those updates out safely across environments is a challenge. Without orchestration, every region or account becomes a separate manual update, and errors slip in easily.

Stacks provide a centralized deployment graph that propagates module updates through defined dependencies. For example, networking updates apply before compute, compute before namespaces, and namespaces before app infrastructure. Deployment groups add another layer of control; teams can promote changes from dev, staging, and prod with approvals or automated rules. This turns complex multi-environment rollouts into a predictable workflow.

Operational Challenges Enterprises Face With Terraform Stacks

The Infrastructure-as-Code market is already large and growing fast: it was valued at ≈ USD 1.06 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach ≈ USD 9.40 billion by 2034, which underscores the scale at which IaC tooling is now used across enterprises.

Fragmented Visibility Across Stacks

Each stack operates within its own boundary. Plans and drift detection are limited to the deployments inside that stack. Once infrastructure is split across multiple stacks, which is common at scale, there’s no native way to see how changes interact across those boundaries. Platform teams often end up validating consistency manually or relying on external tooling to catch cross-stack drift.

Unmanaged and Out-of-Band Resources

Stacks only reflect what is declared inside them. Resources created through the cloud console, ad-hoc scripts, or other IaC tools are invisible to Terraform. Over time, this leads to orphaned infrastructure and configuration drift that stacks alone cannot surface or reconcile.

Learning Curve and Mental Model Shift

Stacks introduce a different way of thinking about Terraform. Teams move from root modules and workspaces to a factory-style model built around components, deployments, and orchestration rules. This requires new files, new syntax, and a new way to reason about infrastructure changes. Adoption often slows down while teams adjust their workflows, reviews, and debugging habits.

Version Upgrade Pressure

Adopting stacks usually means running newer Terraform versions. For enterprises with pinned versions or older modules, this can trigger a broader upgrade effort. Module compatibility issues tend to surface early, and teams often need to refactor legacy code before stacks can be rolled out widely.

Error Handling and Debugging Gaps

Stacks abstract a lot of execution details, which simplifies orchestration but makes troubleshooting harder. Errors can be less clear than in traditional workspaces, and the HCP Terraform UI provides limited visibility into individual component internals. Debugging often requires digging through logs rather than inspecting a single, well-defined plan.

Workflow Constraints

Stacks are designed around a VCS-driven workflow. This works well for most teams but can be restrictive for organizations with custom CI/CD engines, event-driven automation, or tightly controlled deployment pipelines. Integrating stacks into non-standard workflows often requires compromises or additional tooling.

Complex Dependency Graphs at Scale

While stacks reduce manual sequencing, large environments with many linked components and stacks can still become difficult to reason about. Poorly planned dependency graphs increase the risk of blocked deployments or cascading failures. Without careful design, orchestration complexity simply shifts from CI scripts into stack configuration.

How Firefly Complements Terraform Stacks

Terraform Stacks improve how infrastructure is structured and deployed, but once stacks grow in number, platform teams still need a way to understand what is actually running across all environments. This is where Firefly fits in, around stacks, not instead of them, by focusing on visibility, drift, governance, and day-to-day operations.

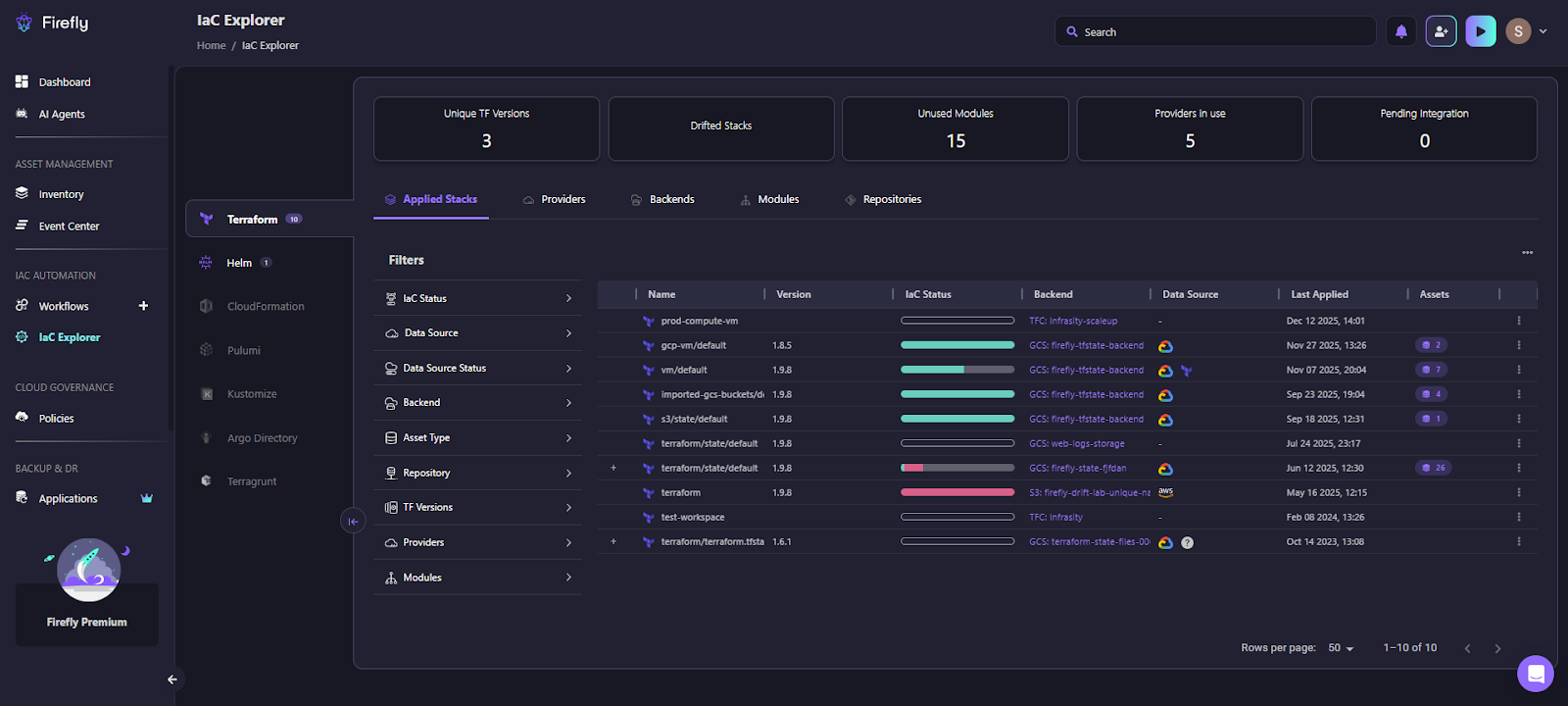

Centralized Visibility Across Stack Deployments

In a stack-based setup, each deployment has its own Terraform state. That isolation is useful, but it also means visibility is fragmented. When you’re operating dozens of deployments across regions and accounts, answering basic questions becomes slow: which stacks are applied, which ones are drifting, which Terraform versions are in use, and where state is actually stored.

Firefly pulls Terraform state from Terraform Cloud and other backends and builds a single inventory across all deployments. This gives platform teams one place to inspect what each stack has applied, without jumping between workspaces or digging through state files manually.

IaC Explorer View of Applied Stacks

The snapshot below shows Firefly’s IaC Explorer focused on Terraform. This view is effectively a control plane for stack-driven environments.

What this view makes visible:

- Applied stacks and deployments: Each row represents a Terraform state tied to a stack deployment or workspace. You can immediately see which deployments are active and when they were last applied.

- IaC status per deployment: The status bar shows whether a deployment is fully managed, partially drifting, or out of sync. This is useful when stacks are spread across teams and regions, and no single Terraform plan can show the full picture.

- Backend and data source details: You can see where each state lives, Terraform Cloud, GCS, S3, and which cloud provider it targets. This matters in mixed environments where stacks coexist with older Terraform setups or different backends.

- Terraform version usage: The summary at the top shows how many Terraform versions are in use across all deployments. This becomes important when stacks introduce newer Terraform versions while legacy workspaces still run older ones.

- Unused modules and providers: Firefly highlights unused modules and active providers across the estate. This helps teams clean up dead code and standardize usage as stacks evolve.

This view gives platform teams operational awareness that Terraform Stacks alone don’t provide. Stacks know how to deploy infrastructure, but Firefly shows what exists, how it’s managed, and where inconsistencies are starting to appear.

Policy and Guardrails Across All Deployments

Stacks don’t enforce global policy on their own. Firefly adds guardrails that evaluate Terraform plans before apply. These checks cover security rules, tagging standards, compliance requirements, and cost impact. They run consistently across all stack deployments and surface feedback directly in pull requests, reducing failed Terraform apply and late-stage fixes.

Drift Detection Beyond Stack Boundaries

Stacks only detect drift within their own state. Firefly continuously scans Terraform states and cloud environments to detect out-of-band changes across all deployments. This helps teams catch console changes, orphaned resources, and configuration drift that would otherwise go unnoticed until the next failure.

How Teams Usually Combine Stacks and Firefly

In implementation, teams usually model:

- One Firefly workspace per stack deployment, or

- One workspace per component, with sequencing handled in CI if needed.

Projects, variable sets, and guardrails are used to mirror accounts, environments, and ownership boundaries. Firefly doesn’t replace Terraform stacks; it gives teams the operational layer needed to run them at scale.

Best Practices for Adopting Terraform Stacks at Scale

1. Design Stacks by Function, Not by Environment

Stacks should represent a stable infrastructure domain, not an environment. In the GCP example, the stack models compute provisioning and authentication once, while dev and prod are expressed as deployments. This allows changes like provider configuration, Workload Identity setup, or VM defaults to be made in one place and rolled out consistently. Creating separate stacks per environment would duplicate this logic and reintroduce the same sprawl stacks are meant to remove.

2. Keep Components Scoped to a Single Infrastructure Responsibility

A component should own one layer of infrastructure that changes for the same reasons and on the same cadence. In the GCP setup, the VM component only creates compute instances and accepts the region as input. It does not configure networking, IAM bindings, or application resources. This keeps dependency ordering predictable (networking first, compute second) and avoids situations where a small change forces unrelated resources to be replaced or re-planned across deployments.

3. Use Deployment Groups to Control Where Changes Land First

When the same stack deploys to multiple environments, deployment groups should reflect the promotion flow. Changes to provider auth, identity configuration, or component logic should run in dev first, then be promoted to prod after review. This is especially important for stacks that manage credentials or cross-account access, where a mistake can block all deployments at once.

4. Plan Stack Boundaries Around Platform Limits Early

Stacks have hard limits on deployments, components, and total managed resources. If the GCP example grows to include networking, IAM foundations, and Kubernetes clusters, those concerns should move into separate stacks. Treat stacks as long-lived units aligned to ownership boundaries. Trying to split a stack later, after many deployments depend on it, is far more disruptive.

5. Treat Drift as an Ongoing Operational Concern

Stacks only reflect what they manage directly. In the GCP case, a VM created through the console or an IAM change made during an incident will not appear in stack plans. Without continuous drift monitoring, these differences accumulate and eventually cause failed plans or unexpected behavior. Drift handling needs to be part of normal operations, not a periodic cleanup task.

6. Add a Visibility Layer as Stack Count Grows

Stacks handle orchestration, but they do not provide a global view across stacks and tools. As platform teams introduce separate stacks for networking, compute, and platform services, it becomes harder to answer basic questions like “what exists in this project” or “what is unmanaged.” A visibility layer such as Firefly fills this gap by mapping cloud resources back to their IaC source or flagging them as unmanaged.

7. Document the Stack Execution Model Explicitly

Stacks change how Terraform is executed and debugged. Document how components are structured, how deployments are named, and how identity flows through the stack. In the GCP example, explicitly documenting the two OIDC audience values prevents repeated misconfigurations and failed runs. Clear documentation reduces onboarding time and helps teams avoid design patterns that don’t scale.

FAQs

1. What is the difference between Stacks and Workspaces in Terraform?

Terraform workspaces only provide state isolation and operate independently, so Terraform has no understanding of dependencies or execution order between them. Terraform Stacks, on the other hand, add a deployment and orchestration layer that manages dependencies, enforces run order, supports promotions across environments, and still maintains an isolated state per deployment.

2. What are the components of Terraform Stacks?

Terraform Stacks are composed of components that wrap standard Terraform modules, deployments that define where and how often those components run, stack-level provider configuration for consistent authentication and regions, and an execution graph that automatically enforces dependency order between components.

3. What is the difference between a template and a stack?

A template is a static blueprint or starting structure that must be copied or instantiated manually and has no execution or lifecycle awareness. A stack is a live, managed deployment model that defines infrastructure, environments, identity, dependencies, and execution flow, all orchestrated by HCP Terraform.

4. What is the use of Terraform Stacks?

Terraform Stacks are used to deploy the same infrastructure consistently across multiple environments, regions, and accounts, to enforce correct dependency sequencing, to securely model authentication using short-lived credentials, and to enable controlled, predictable rollouts of platform changes at enterprise scale.